Dear Friends

Back in December, I shared some reflections about 2022 and some predictions for 2023. So far, those predictions seem (to me) right on, though I was too optimistic about “the end of COVID.”

If I’m truly considering a book about the next 25 years based on the past 25 years, I should put my cards on the table about where I think we’re headed:

No, I don’t think that the world, or even the United States, will reach net zero emissions by 2050 when I am 70 years old, but I think that we’ll get close and that by 2070 we’ll have used a combination of carbon capture and reflective particles to get the climate back to what it was like in 1950. (I’ve set a reminder to check on this when I’m 90!)

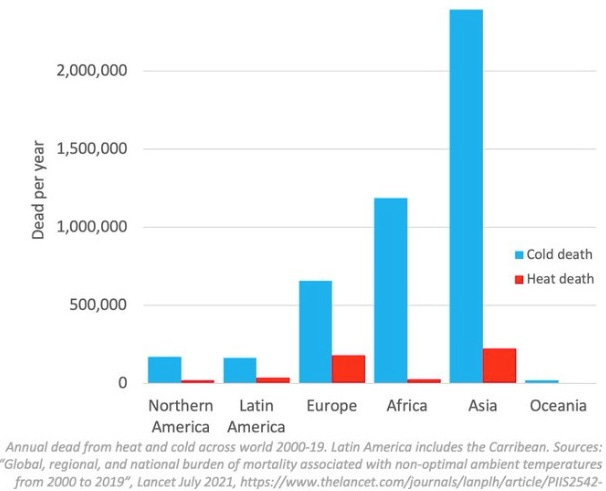

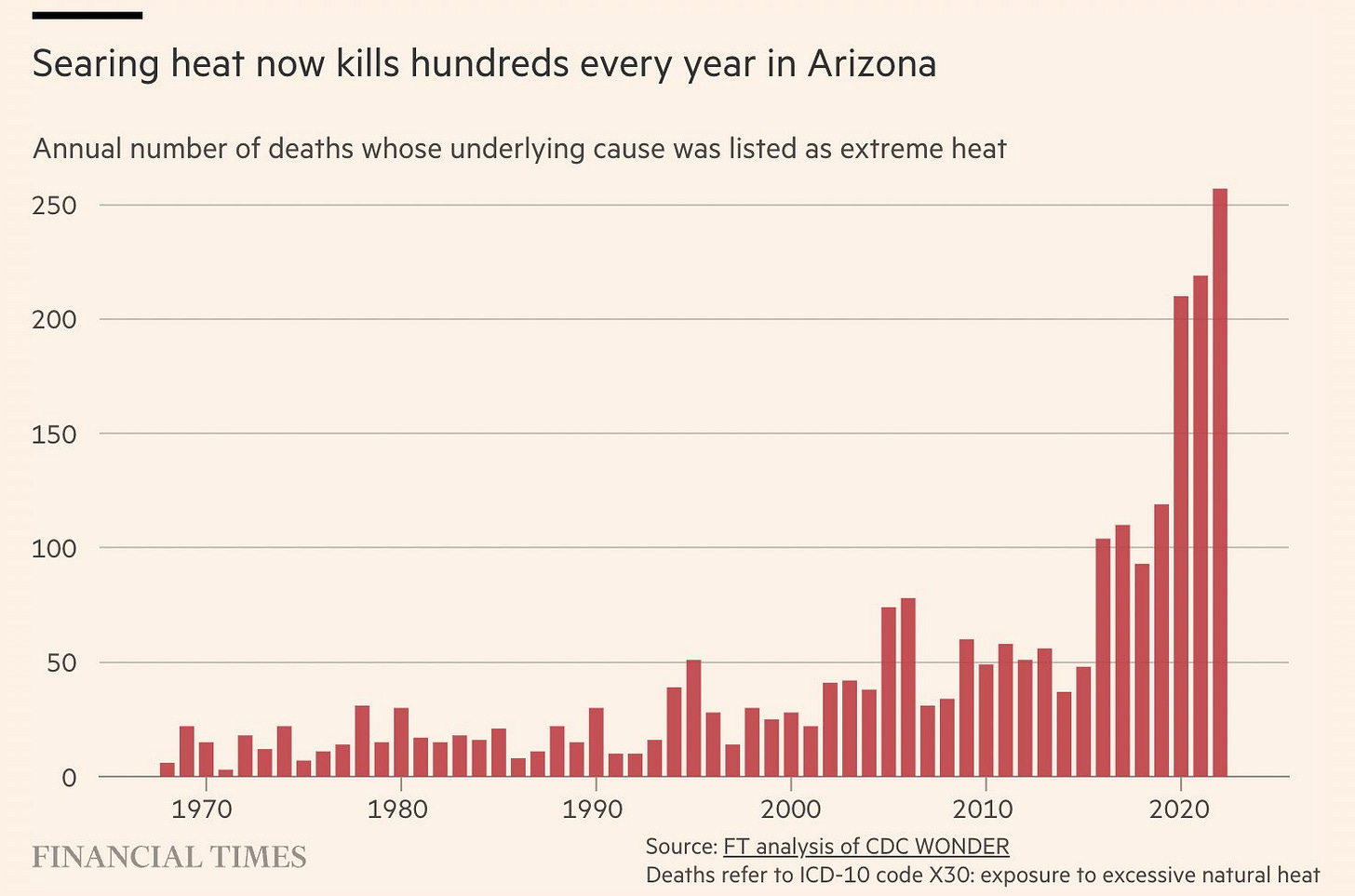

I think that the average temperature will continue to go up ever so slightly over the remainder of my lifetime and that more people will want to move to slightly cooler places, which will help counter-balance the migration we’ve seen to warmer, sunnier places over the last 100 years — and especially over the past three years. I think that slightly rising temperatures will lead to fewer climate-related deaths over the next fifty years1 and that we’ll look back at the New York Times reporting about climate-related economic loss ($500 billion) as laughably wrong because the economy will have transformed in unpredictable ways by 2050. I think we’ll see a modest (like 2%) increase in the number and severity of hurricanes, floods, and wildfires.

I’m not a climate denier. The planet is obviously warming —just like climate models mostly predicted. But the models have also gotten plenty wrong — for instance, they don’t know why the Pacific Ocean is cooling or how cloud cover affects temperature variation.

Last year, the three fastest-growing large cities in the U.S. were Forth Worth, Phoenix, and San Antonio. Nearly all of the fastest-growing cities over the past four years are in the warmest parts of the country.2 In 2016, the average house for sale in Phoenix cost $200,000. Today, it’s over $400,000. Clearly, Americans are not factoring climate change into their decisions about where they choose to live and invest.3

Over the next 25 years, I think that we’ll spend an unprecedented amount of money building out solar and wind farms, and hydropower dams.4 I imagine that the biggest obstacle will continue to be a lack of workers — not investment — and that the unemployment rate will stay below 5% for the next 25 years.

But I don’t think we’ll ever return to the days when more than 65% of Americans were working. As the population ages and the economy becomes more productive from AI and robotics, I expect the labor force participation rate to dip below 60% by 2030 and below 50% by 2050. Even with increased immigration, I think we’ll continue to see labor shortages in healthcare, education, and tourism/hospitality.

Today, nuclear power generates around 10% of the world’s electricity and the IEA forecasts that the figure won’t change much by 2050. I think that a nuclear fusion breakthrough is likely over the next decade and that a next-generation nuclear startup like Oklo (or one of its dozens of competitors) will find Tesla-like growth so that nuclear could represent 50% of electricity generation by 2050.5

The EIA says that the world's consumption of energy will grow by 50% from 2018 to 2050. I think global demand for electricity will be far higher — at least double what it is today — as power-hungry AI systems process larger amounts of data than we can imagine today.6 Also, most of the 10 billion humans in 2050 will grow up with Insta-dreams of owning electric vehicles, air-conditioning, and traveling the world in electric planes. And yet, despite the crazy increase in demand, I still think the cost of electricity will come down. Electricity prices have increased 2.3% per year in the United States for the past 25 years —roughly on par with inflation. By 2030, I expect the cost of electricity to start to decline. And by 2050, I think electricity will be so cheap that we’ll never think about it.7

In fact, I think that electricity will be so cheap and abundant by 2050 that the children of Gen Z will struggle to understand why we covered so much of the world with solar panels, wind turbines, and hydro-dams. By 2050, the cost of maintaining that renewable infrastructure could be higher than the value of the electricity they generate. And so it will be the next generation’s mission to remove and recycle all of that heavy, rusting equipment, re-wild the environment, and reintroduce animals to their old habitats (much as is now happening with wolves in Germany.) This video by Semafor about the recent renewable infrastructure construction in Texas helped me realize what a massive project it will be to remove renewable infrastructure once we no longer need it:

You’re probably thinking that this is a pretty optimistic prediction about the state of the world in 2050. Not for me. The world that I want to live in come 2050 is happier, slower, healthier, and more in tune with nature. We would be less distracted and feel more connected to each other. We would spend more time in creative flow states and less time worrying about the latest outrage drummed up by some fearmonger or “conflict entrepreneur.”

But that’s not what I expect. I think that it’s deep in our nature to worry and focus on threats more than beauty and wonder. It is in our nature to be more concerned about what others think of us than how we can connect with them. We prefer to watch Netflix or play video games than risk feeling rejected when asking a new friend to hang out. Most of us like the idea of nature and how it makes us feel, but then we find endless excuses to avoid it.

I don’t expect any of that to change much by 2050. Therapy and coaching will become more common but any progress toward happiness, healing, and fulfillment will be slower than the pace of technological innovation. The children of Gen Z will find plenty of reasons to be outraged and unhappy in 2050: How could we have possibly murdered so many animals throughout our lifetimes, especially with factory farming? Why did we cover the planet with wind turbines and solar panels that turned out to not be entirely necessary? And of course, there will be raging debates about migration, genetic engineering, predictive policing, who gets to travel to space, and whether children should grow up with AI nannies and friends. Occasionally, we’ll celebrate the massive decrease in deaths from malaria or during childbirth, but mostly we’ll continue to focus on the negative: for instance, how young working parents must support an aging population — and raging debates about whether it should be legal to eat meat.

The thing I’m least optimistic about between now and 2050 is our capacity to feel fulfilled.

When I graduated from college in 2003, nearly 70% of Americans were satisfied with the way things were going in the US. Today, it’s less than 20%. Noah Smith published an insightful post looking at how all the usual objective measures of “American satisfaction” have improved even as Americans are increasingly dissatisfied, depressed, lonely, and drug-addicted. He concludes the piece by noting that he’s making these comparisons not to “lecture Americans on why they should be happier with the economy they have.” But rather: “It’s to figure out how to make them happier.”8

If I do decide to write this book, I’m thinking that a central premise (or perhaps the concluding chapter) will explore the growing discrepancy over the past 25 years between our objective well-being and our subjective dissatisfaction with how we feel.

👏 Kudos: Iris Calderon, immigrants, and lifelong learners

When Iris and I first moved to San Francisco from Seattle in 2016, it became our Sunday routine to head to Flora Grubb Gardens — a plant nursery with a cafe — for our morning coffee and creative time. The plants, the design, the landscaping, the vibe: immediately we felt relaxed and inspired.

By 2019, she experienced what is common among educated, highly-skilled immigrants: she struggled to find the kind of industrial design job she was trained for because she lacked an American credential, didn’t speak English perfectly, and didn’t have a local network of references. (No hiring manager, she learned, is willing to speak to a reference in Mexico through imperfect English.)

It’s not easy for a successful industrial designer in her 30s (who already founded two successful companies in Mexico) to take a cashier job in retail, but we needed the money to pay the bills. So she figured, well, why not the plant nursery where at least she liked the vibe? And maybe she’d learn a thing or two about plants.

Did she ever. Iris is a dream hire for a small-business owner; she’s the type of person who isn’t just quick to ask “What else can I do?” but has her own smart ideas about what ought to be done. Now she’s the one responsible for the store’s design … for giving it that same inspiring feeling that first attracted us nearly eight years ago. And not just for the San Francisco store; she spent the first half of this year traveling constantly to Los Angeles to design their new store in Marina del Rey.

Iris and I have different interests but we’re united in our passion for lifelong learning. When she takes a week off from work, like she is doing this week, it’s to enroll in a weaving workshop. And even then, she wakes up early to catch up on classes from her dry garden design class.

We have been together for 14 years now, and I see how Iris as an immigrant has had to work harder than most, though it has never turned her bitter. And while I know that celebrating hard work has become passé in 2023, I can’t help but admire it. I think what I admire most is the type of confidence it has given her — not the arrogant confidence of thinking that she can do anything, but the persistent confidence of knowing she can learn just about anything. From a recent James Clear newsletter:

“One version of confidence is: I’ve got this figured out.

Another version is: I can figure this out.

The first is arrogant and close-minded. The second is humble and open-minded.

Be humble about what you know, but confident about what you can learn.”

☎️ Survey says: Data, death, and immortality

Participation in last week’s poll was lukewarm. Only 15 people voted. No topic got less than two votes or more than four votes. Basically, “Who cares, write whatever makes you happy.” And so I’ll try drafting a newsletter about death, data, and immortality. And if I’m not having fun, then I’ll write something else. 🤷♂️

As always, I appreciate you reading. And I especially appreciate those conversations and emails when we talk about something that resonates with you.

Have a great week!

David

You probably read about Bangladesh’s record-breaking floods last year, but there was little mention of the massive decline of flood-related deaths in Bangladesh since the 1980s.

My former colleague Jane Flegal offers the following quote from a report on climate adaptation. “While economic models may predict that humans will act like optimizing agents who move to more productive parts of the country, in reality, humans have instead acted like humans, who are attached to their struggling communities.” My friend Ted responds: “True. Also true that something like a third of the US population has moved from Rust Belt to Sun Belt over the last 50 years, so…”

There is an upside to Americans moving to places with higher temperatures, as they then live closer to the biggest solar electricity farms in Texas, Florida, Arizona, and Nevada.

We already are. My favorite website of 2023 shows a map and chart of the real projects funded by the IRA and CHIPS acts and how many jobs each has created.

This is a wildly unconventional prediction that should prompt eye-rolling skepticism; the IAEA says nuclear will contribute just 12% as a best-case scenario

Then again, I also expect most of the data in the cloud to be processed by energy-efficient quantum computers by 2040.

Kind of like the cost of flat-screen TVs. Iris and I visited the house of a middle-class, rural construction worker in Oaxaca who built himself a four-story, 6-bedroom house and he had a flat-screen TV in every room for his family of three as if they were art pieces.

Noah is at the peak of his game when he takes a small piece of pop culture — a two-minute campaign ad, or a three-minute viral YouTube country song — and does a deep dive into the statistics and policies it breezily touches on.

One of your best posts, interesting throughout, thank you.

Copy, pasted, and sent to group chat what resonated with me. Yeah, Iris!