Will aging, shrinking, rich countries welcome young, skilled Africans workers?

And will Africans want to leave?

Dear Friends,

Why was I motivated to write 2,800 words (and 18 footnotes! 🫣) about depopulation, migration, and the future of work? And how could I possibly persuade you to spend 15 minutes of your busy day reading them?

I wrote this during my last work trip to Ghana, mindful that I won’t work on African issues for at least another decade — so I wanted to leave myself a time capsule with some of the questions and insights that I’m taking with me. Why might you be interested? Because ours is the first generation ever to witness the start of a long-term shrinking of our species with radical implications for how we age, retire, migrate, and fill vacant jobs. With or without climate adaptation, the “great age of migration” is upon us and it’s feeding ethnonational resentment just about everywhere. As I write this, the front page of the Wall Street Journal warns that “a global shortage of healthcare workers is setting off a bruising worldwide battle for talent, as rich countries raid other nations’ medical systems for staff to care for their aging populations.” Not a day goes by in California without warnings of a severe teacher shortage. And the front page of the New York Times shows a photo of migrants lined up outside of the Roosevelt Hotel in New York City, hoping to be placed in a shelter. Even while nationalist populist leaders criticize immigration, their economies still depend on migrant labor.

In the first section, I cover some of the big demographic shifts: where populations are shrinking, growing, and clustering. In the second section, I offer my predictions about the future of work and how we can train enough nurses, teachers, and builders when already we struggle to fill vacancies. Next, I cover some of the recent contradictions in the politics of immigration — focusing on the UK, Ghana, and Canada as three countries that are representative of political dynamics at play in East Asia, Europe, and North America — and how they depend on African migrant labor. Finally, I conclude by showering some love on the Global Skills Partnership as a model of international cooperation that builds popular support for legal migration by providing migrants with the skills needed to contribute to their new countries.

Preparing for a shrinking planet

They say that our species has been around for 300,000 years. So, let’s call the average generation between parent and child 20 years1 — that would give each of us somewhere around 15,000 direct-lineage ancestors. What a trip. And yet the total human population barely budged until the Industrial Revolution:

Next month, Iris and I will celebrate my grandmother’s 94th birthday in Seattle.2 When she was born in 1929, the world’s population was two billion. Today it is eight billion. Can you imagine? Over her lifetime, the world’s population quadrupled and the world’s total GDP increased 20x. What a time to be alive!

Ours is also an exciting time to be alive3 but for different reasons. Of the 15,000 or so generations of Homo sapiens, ours may be the first to witness a shrinking human population.4 Europe and East Asia have started shrinking first, Latin America isn’t far behind, and North America is dependent on immigration to keep our population growing.5

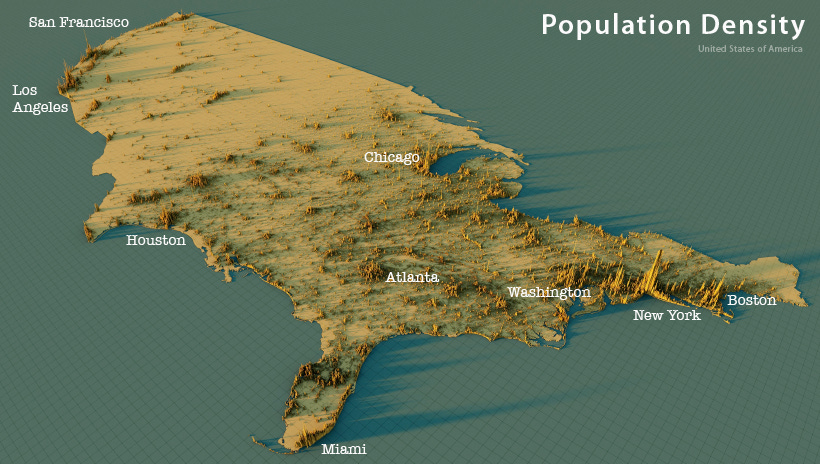

Few realize that the population growth rate reached its peak in 1963 — five years before The Population Bomb was published. You can see in the chart above that the human population will continue to slowly grow from eight to 10 billion over the next 50 years before it begins to contract. So where should we expect these extra two billion people to live? That depends a lot on climate change, urbanization, and immigration policies. If you’ll indulge my geeky affection for population density maps, cities, and train travel, here are a few ideas:

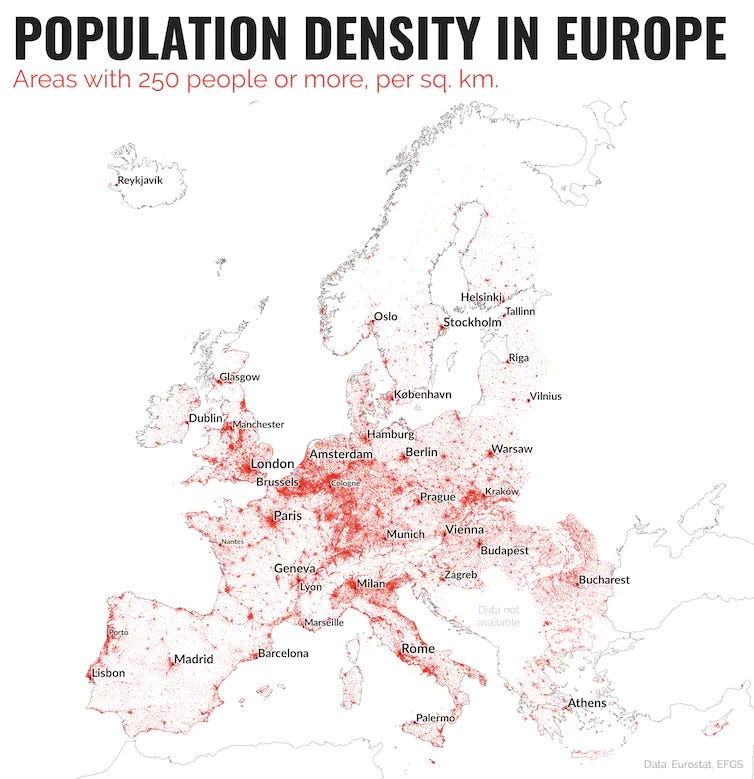

Think about the most populous corridors of the world. There’s the busy, humid Amtrak corridor between Washington DC and Boston. In Japan, I love the Shinkansen corridor between Tokyo and Osaka with epic Mt. Fuji in the background. In China, a bullet train will take you 1,000 miles through China’s metropolitan belt from Shanghai to Shenzhen in less than 10 hours for less than $100. Most of Europe’s population, as you can see below, concentrates along an 800-mile corridor from Rome to Amsterdam, though it will take you 15 hours by train with at least two transfers.6

All of these population corridors, however, pale in comparison to what is taking shape along coastal West Africa between Abidjan and Lagos — a 600-mile stretch that Howard French calls “the world’s most rapidly urbanizing region, a “megalopolis” in the making.”

The West African Megalopolis is built atop three converging forces: relatively high fertility rates, urbanization, and globalization. Young people growing up in rural West Africa are drawn to cities by viral content on their smartphones and job opportunities linked to international ports and airports.7

As you can see in the chart above, by 2045 Africa will grow by 40 million people per year; whereas Europe will lose nearly 2 million people per year and Japan will lose 740,000. There is plenty of land Africa to accommodate an additional 40 million people each year, but will the aging populations of Europe and East Asia survive without young migrant workers?

How will the next 2 billion people work?

One of the weirdest parts of living in San Francisco between 2015 and 2020 was how rarely I saw any children. In Ghana, children are everywhere. As Howard French writes during his road trip through West Africa:

Most noticeable of all were the schoolchildren walking the streets in their uniforms and backpacks. By 2050, about 40% of all the people under 18 in the world will be African, a proportion that will reach half by the century’s end. On the streets of Kasoa, statistics like these come to life. Everywhere there were billboards for daycare centers, kindergartens, and “international schools”.

What will these children be doing for work in 20 years as adults wanting to provide for their own children? The standard development path is agriculture > manufacturing > services > software > pilates classes & keto diets. But in the context of globalization and cheap imports, most African countries have struggled to compete in agriculture or manufacturing, much less services and software. The conflict in Tigray dashed any hopes that Ethiopia could compete with Vietnam, India, or Mexico as multinationals hedge against Chinese manufacturing. A record $5 billion was poured into African startups last year, but so far they aren’t creating jobs or profits.8 For a while, there was hope that Africans would do the grunt work of training AI models, but most of those short-term contract jobs are now moving to Nepal, India, and the Philippines.9

It’s anyone’s guess what the global job market will look like in 2045, and here’s mine:

More nurses, doctors, and caretakers for an aging population

More teachers, camp counselors, nannies, and coaches for stressed-out parents

Builders and engineers to fix aging infrastructure, install renewable energy, and build new housing for those additional 2 billion humans

Content creators and influencers in lieu of traditional advertising

Tourism, hospitality, wellness: Tour guides, spas, foodie tours. Therapists, life coaches, creativity coaches, longevity coaches, and retreat staff for a lonely, wealthy, aging, secular society

As AI advances, I don’t expect nearly as many jobs of the kind I had over the past 20 years: sitting at a computer, reading PDF documents, analyzing budgets in Excel, and writing memos with recommendations. And how will people gain the skills for future jobs? I expect more practical training from YouTube and on-the-job mentors than from traditional 4-year universities.

The contradictory politics of migration

We are in an untenable situation in which rich countries with shrinking, aging populations don’t want to let in more immigrants while the residents of poor countries with growing, young, and jobless populations want to leave. According to 2021 polling data by Gallup of more than 100,000 people in 122 countries, 900 million people say they would like to permanently move to another country, a stark increase from when Gallup first asked this question in 2011.

In 2018, Afrobarometer asked 45,000 Africans from 34 countries if they have seriously considered migrating to another country, and 37% (mostly young people) said they have. If all those people were to leave, Gallup estimates, “Sierra Leone would lose 78.0% of its youth population and Nigeria 57.0%.”

“We are entering the age of migration,” writes Britain’s former Secretary of State and leader of the Tory conservative party. “Measured in numbers of people, this is likely to be on a scale never known in human history.” Already, a massive increase in the number of foreign born nationals in the past 20 years has caused anti-immigration political backlash in Europe and the US, as David Leonhardt describes in the New York Times:

Even nationalist conservatives need immigrants to survive

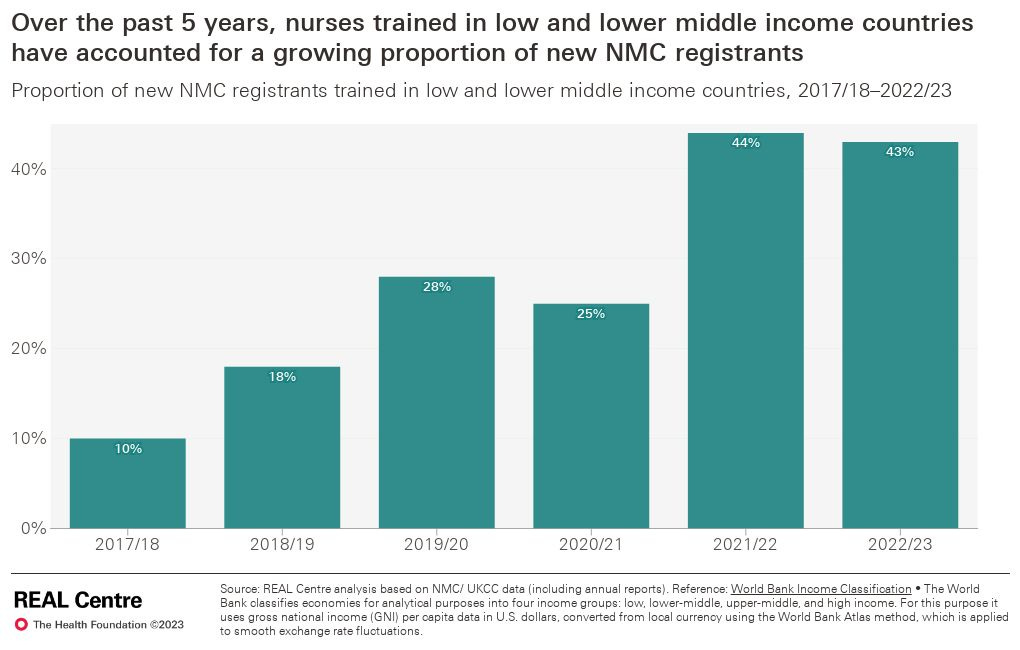

I’ve been keeping my eyes on two parallel crises in the UK rooted in the country’s aging demographics.10 Over the past six months, more than 12,000 migrants have arrived to Britain by boat and another 50,000 could arrive this summer.11 The resulting backlash prompted a plan by the conservative government to deport all new migrants to Rwanda, no matter what country they’re from. At the same time, Britain’s 75-year-old National Health Service is falling apart, as nurses and doctors have not been able to keep up with the country’s aging population. And so even while the government says they will cut down on immigration, they actively recruit thousands of Ghana’s most experienced nurses.

So there you have it: the UK’s Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, whose parents immigrated from East Africa in the 1960s, tasked his Home Secretary Suella Braverman, whose father was a refugee from Kenya, to implement a plan to deport all asylum seekers to autocratic Rwanda. Meanwhile, the woman who took over the National Health Service in the midst of the pandemic is entirely reliant on nurses from Nigeria and Ghana (as shown in the graph below) to attend to a record wait list for medical care.12 More than 7.2 million Brits are currently waiting for medical care, and the government has routinely missed its target to bring down wait times for elective operations below 18 months. One in ten Britons have done DIY dental work because they can’t get an appointment. As if that weren’t bad enough, doctors are now striking for better pay and more rest.13

Nearly half of new nurses in the UK were trained in low and lower-middle-income countries — mostly India, the Philippines, Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya. (Semafor published a fascinating look at scams in Zimbabwe as young women seek nursing certificates to flee economic turmoil.)

The UK is not the only country whose political leaders espouse anti-immigrant rhetoric while their public services and economic policies depend on recruiting immigrant workers. Italy has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world with a population that is expected to 1) age significantly, and 2) lose 10 million people by 2050. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni was voted into office on a campaign with frequent anti-immigrant, ethnonational slogans. And yet despite the rhetoric, Meloni’s government increased the number of non-EU work permits to fill hiring gaps at hotels, hospitals, and construction sites. Italy’s struggling economy and declining population wouldn’t survive without them.

Sensible migration policy is sensible development policy

In the UK, US, and across Western Europe, voters have become more right-wing, nationalistic, and anti-immigrant amidst rising percentages of foreign-born residents. Many pundits pinned Hillary Clinton’s defeat on her pro-immigration stance, worrying that the same could befall Biden. And yet, even conservatives like William Hague know that recruiting immigrants is at the foundation of any successful economic policy:

The US is the outstanding model of the crucial role of migration in bringing economic and technological pre-eminence. It is a powerful reason why America will ultimately see off the challenge of China, a much more closed society.

Indeed, beyond big names like Elon Musk and Sergey Brin, a recent study found that “immigrants have started more than half of America’s startup companies valued at $1 billion or more.”14

So, is there an alternative to populist politicians who thrive on anti-immigrant rhetoric while their economic policy depends on recruiting immigrants? Could Canada — with its rapid rise in immigration — have the answer? Derek Thompson suggests in the Atlantic that if the US could just adopt Canada’s multicultural tolerance, we’d be better off economically. Noah Smith suggests that Canada’s calm openness to foreign-born residents rests on a policy of only admitting highly skilled and educated immigrants. And Matt Yglesias builds on Smith’s argument — noting that Canada’s pro-immigration government rejected 90% of asylum claims filed by Haitians. Yglesias argues that progressives in the US ought to learn from Hillary Clinton’s loss and not appear soft on illegal immigration. By cracking down on illegal immigration, as Biden did earlier this year, Yglesias hopes that there will be more popular support for a Canada-like increase in the number of work visas granted to immigrants and legal pathways to citizenship.

What might that look like? Could the US and Europe provide the needed skills to future migrants that fill our gaps in the labor market? A study by the federal government projects a shortage of 80,000 nurses by 2025.15 Where might they come from? In Ghana, it costs roughly $1,000 to finish nursing school, after which a registered nurse can expect to make between $4,000 to $6,000 per year. In the US, nursing school is increasingly free, and a registered nurse can expect to make $80,000 per year.

In theory, you could train the missing 80,000 nurses in Ghana for just $80 million — around 1.5% of this year’s budget for the United States Agency for International Development. I don’t mean to breezily dismiss the complexity of scaling up nursing education in Ghana, but you get my larger point.16 And it’s not just nurses: The Economic Policy Institute projects a shortage of 300,000 teachers by 2025. The construction industry hopes to attract another 500,000 builders this year alone. And TSMC’s $40 billion investment in a chip manufacturing plant in Arizona has been delayed yet again because it can’t find enough qualified and willing workers.

The US, Europe, and East Asia need to build a talent pipeline to address a systemic labor shortage and an aging, shrinking population.17 There simply aren’t enough Americans, Europeans, or East Asians to fill the demand for labor; they are growing older, wanting to work less, and retire sooner.18 Fortunately, some smart folks at the Center for Global Development have been working for over a decade to develop a Global Skills Partnership to “meet global skill shortages by providing targeted training in countries of origin and helping some of the trainees move.” Last year, Hannah Postel published a case study of the idea, which was first discussed in 2005 and became concrete in 2014 when Michael Clemens published a prescient paper focused on training nurses in poor, youthful countries to migrate to rich, aging countries. Shortly after Clemens’ paper, some real programs were designed to test out the idea — including between construction workers in Kosovo looking to work in the EU and hospitality workers in the Pacific Islands wanting to work in Australia. And there is a new pilot focused on providing vocational training to young people in Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt interested in working in Germany or Belgium.

COVID disrupted all of these carefully planned programs, making them difficult to evaluate. (COVID also changed the way we work, as

explores in her forthcoming utopian novel, opening new possibilities for remote work across borders.)I loved Hannah Postel’s case study of the past 15 years of the Global Skills Partnership, but it left me uninspired with its concluding summary of skepticism. What is our best hope for the next 15 years of the Global Skills Partnership, and might there be a role for me to help advance it? Perhaps Claudia Sheinbaum will be elected Mexico’s next president in June and a friend is appointed to a senior position in Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs tasked with negotiating migrant and trade policy with the United States. Then, if Biden is re-elected in November perhaps the Department of State and USAID will explore ways to reduce illegal immigration while increasing legal migration of skilled immigrants who learn English and can help fill labor shortages in nursing, construction, teaching, manufacturing, eldercare, and childcare. Maybe there is room for me as a consultant to help design a pilot program that provides much-needed vocational training in Mexico to fill some urgent labor gaps in the United States. 🤔

To conclude: Europe’s population was expected to peak in 2026, but it might have already happened with consecutive years now of population loss. By 2050, one of every three East Asians could be above 65 and Africa’s population is expected to double from roughly 1.2 billion today to 2.4 billion. Wealthy, aging, and shrinking countries must do more than just incentivize their current citizens to have more children. They should invest in the workers of tomorrow who are young people today in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America through training and vocational programs that offer legal and controlled pathways to immigration.

And with that, friends, Iris and I are off to Pittsburgh to celebrate my cousin’s wedding. Next week’s newsletter will be not so long, not so serious.

Many thanks to Yonathan, Engin, and Emily for their feedback on a draft and to Justin Sandefur for pointing me to the Global Skills Partnership.

Have a lovely week,

David

The average age of childbirth was surely much younger for most of that time.

She still plays in a jazz band and will perform at my cousin’s wedding this weekend! The real reason that Milan Kundera’s death hit me so hard is that he was born the same year as my grandmother.

I have been alive for nearly half of my grandmother’s lifetime, so it’s not like there hasn’t been any overlap, of course. :)

Granted, current projections estimate that the world’s population will start to decline in 2086, which means I’d have to live until 106, though fertility rates are falling in Africa faster than anyone expected causing demographers to revise their estimates.

How much can we trust these projections? Past UN projections have been remarkably on target.

The West Coast of the US has three density corridors: from Tijuana to Los Angeles, Monterey to Sacramento, and Portland to Vancouver … but the train journeys are too slow and inconsistent to merit mention. Most of India’s fast-growing population stretches 650 miles from New Delhi to Patna; a direct train journey takes about 12 hours.

Ironically, the migration of young people from villages to cities is also reducing Africa’s fertility rate faster than demographers expected: In urban Nairobi, for instance, the average woman has 2.5 children compared to 8 in rural Mandera County.

Twitter closed its Ghana office and still hasn’t paid out severance.

Now Ghana wants to compete in the industrial production of marijuana, but I can guarantee you they don’t have a chance if they cap THC at .3%!

As if their runaway inflation and rising mortgage payments weren’t bad enough

There was an uproar over how much the government was spending on hotels to house the migrants, so they will move them to tents.

Ghanaians meanwhile complain about the UK’s restrictive immigration policies while also complaining about stealing their best nurses while also deporting asylum seekers from neighboring Burkina Faso. The contradictions on views about immigration run deep and are mostly self-serving.

While parliament negotiates doctors’ salaries, private equity has taken over a recruiting firm that contracts NHS employees outside of their regular working hours to provide care to patients at private hospitals.

Even more impressive: “Nearly two-thirds (64%) of U.S. billion-dollar companies (unicorns) were founded or cofounded by immigrants or the children of immigrants. Almost 80% of America’s unicorn companies (privately-held, billion-dollar companies) have an immigrant founder or an immigrant in a key leadership role, such as CEO or vice president of engineering.”

Reforming US development policy might be even more challenging.

There is a valid critique that training programs linked to immigration channels could drain Africa of its most talented health workers, teachers, and builders to which I have three responses. First, not everyone is going to want to leave; many Mexican migrants return home after discovering that the money isn’t worth the hustle in the US. Second, even today African migrants send home more money in remittances than Africa receives in foreign assistance. Third, many of Africa’s most successful entrepreneurs started out in the US and Europe before returning home to take advantage of a bigger, growing market.

Even if AI were to automate away most of the knowledge economy, transport, and manufacturing, the unprecedented productivity gains will shift the profits somewhere creating new forms of labor and welfare payments that are impossible to predict today.

So well done, David.