12 (Mostly Optimistic) Reflections about 2022.

Also, a playlist and some surely terrible predictions about the next decade

Dear Friends,

“Music is, to me, proof of the existence of God,” wrote Kurt Vonnegut. What else affects our mood so potently without any obvious evolutionary explanation? There were many albums this year that potently affected my mood, among them:

Big Thief’s double EP Dragon New Warm Mountain | Believe In You. There is something about Adrianne Lenker’s voice that makes me want to bliss out on a picnic blanket with a thermos of peppermint tea and a joint. Iris and I saw them live at the Fox Theater in May. In my journal that night I wrote, “Glad we went to the Big Thief show this evening. They played Shark Smile. And my favorite song, Cattails. I felt a deep love for Iris by my side.”

Kendrick Lamar’s Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. By far my favorite rapper and street poet laureate of the past decade. No one else — not 2pac, not Kanye — more creatively transforms anger into art. My pulse quickens every time I listen to the track Father Time with Sampha.

Dijon’s Absolutely. Okay, this officially came out at the end of 2021, but I didn’t discover it until this year. I guess I was looking for a new Frank Ocean album that sounded a bit more like Bon Iver. This is it. I’d add “The Dress” and “Big Mike’s” to my top-100 list of love song lyrics if I were to have such a list.

Beth Orton’s Weather Alive. Her 1999 album Central Reservation was one of 30 or so CDs on rotation as I drove down from some misadventures in Alaska, where I dreamed of being a novelist mountaineer, to the humbling resignation of community college and working at 7-11 in San Diego. I know every lyric of every song on that album and I had a massive crush on the freckly, pixie-cut girl on the cover. I love that she broke Ryan Adams’ heart and that he wrote a clever song as a pathetic attempt at lyrical revenge. This album is everything I would expect from a 51-year-old Beth Orton: mature, subtle, patient, and unpredictable.

Grace Ive’s Janky Star is a very different kind of album: fun, irreverent, young, and a little tipsy. “I look at pictures of real estate; I see the ad and take the bait … I watch that movie ten times a day; I can recite it; you press replay … If you get up, can you shut the light? That’s the first star I’ve seen all night.” Apparently, she wrote most of these songs while working the coat-check at an indie music venue in Brooklyn and that’s exactly how it sounds. Whereas Beth Orton’s Weather Alive contains all of the wisdom and disappointment accumulated by 50, Grace Ives bemusedly shrugs at the drunken missteps of youth.

Here’s a playlist of some of my favorite tracks of 2022. It follows my usual playlist structure: Rock then R&B then rap then electronic dance and finally some quiet lullaby-like ballads.

Let me know what I missed. And please let me know if you’ve made a 2022 playlist. Thanks to friends who shared their favorite 2022 albums with me, including Aquila, Damon, Marsha, Revaz, Ali, and Laura.

12 Reflections about 2022

I’m a sucker for year-end reflections and best-of lists. I thoroughly enjoyed the Wall Street Journal’s Year in Review and the New York Times’ Year in Pictures. The Economist gets my vote for the most concise summary of 2022. And huge props to Kimberly Mas and the team at Vox for their smoothly edited “2022, in 7 Minutes” video. (I love their insertion of TikTok triptych reactions to news anchors reporting what would become the year’s biggest stories.)

As I read, I was inspired to jot down my own list of 12 reflections about 2022 with a reminder to revisit them a decade from now to see what I got wrong and right. Here goes:

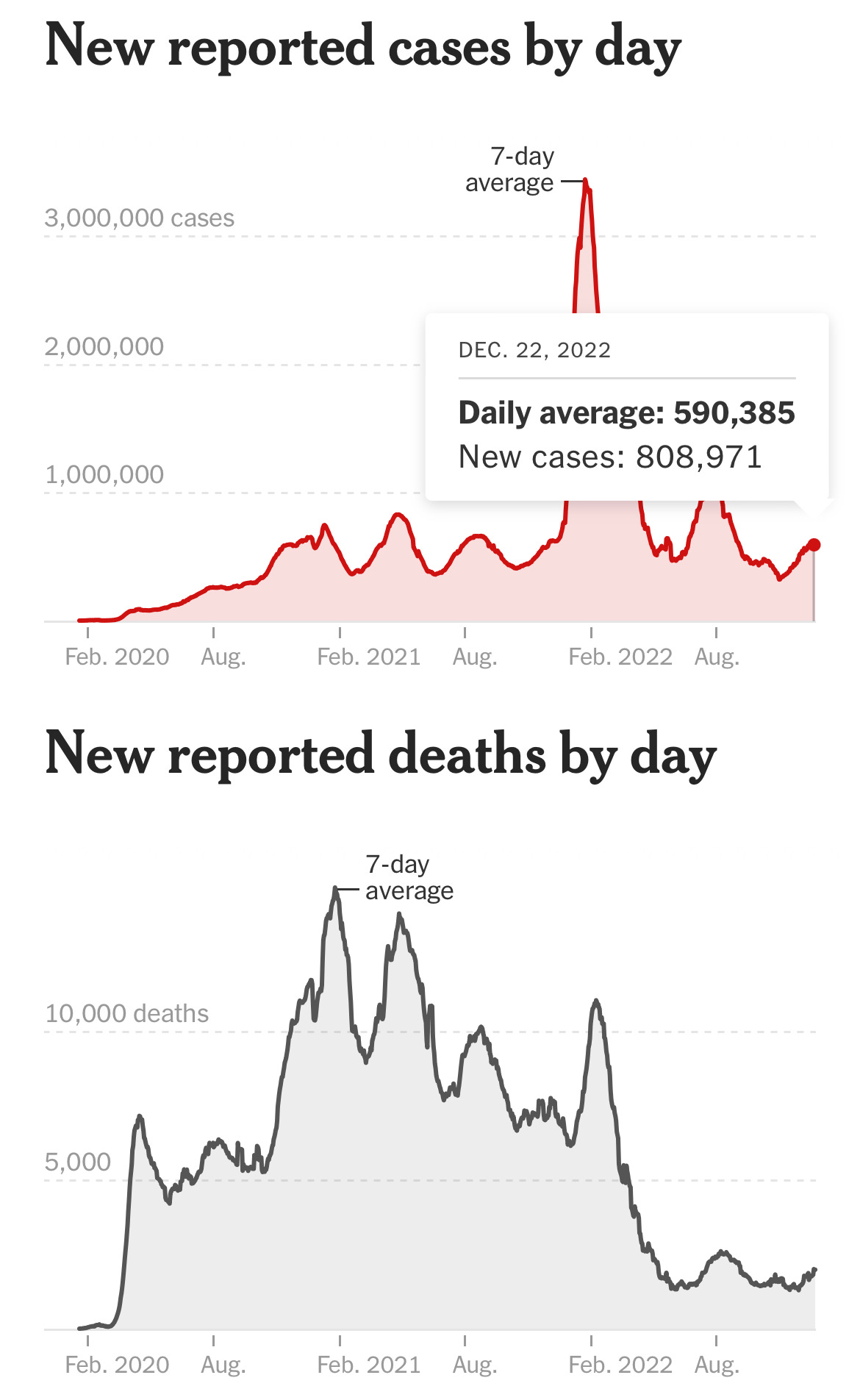

The end of the COVID-19 pandemic? In April 2020 Arundhati Roy wrote an essay about the pandemic as a portal to remake the world. At the time, there were around “only” 75,000 daily cases of COVID worldwide and we were scared to leave our homes. Today, there are over 500,000 new cases each day, and airports are stuffed with surly travelers. More than 6 million people have died from COVID. Did we overreact at first? Are we under-reacting now? How many people would have died were it not for the astonishingly fast development of vaccines? In the early days of COVID, we read about the mostly forgotten history of the 1918-1920 Spanish Flu. I assume that future historians will call it the 2020-2022 COVID-19 Pandemic. Or maybe not. Maybe more Chinese will die from COVID next year than during the previous three years? In her 2020 essay, Roy concluded: “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.” Perhaps 2022 was the first year of the new world.

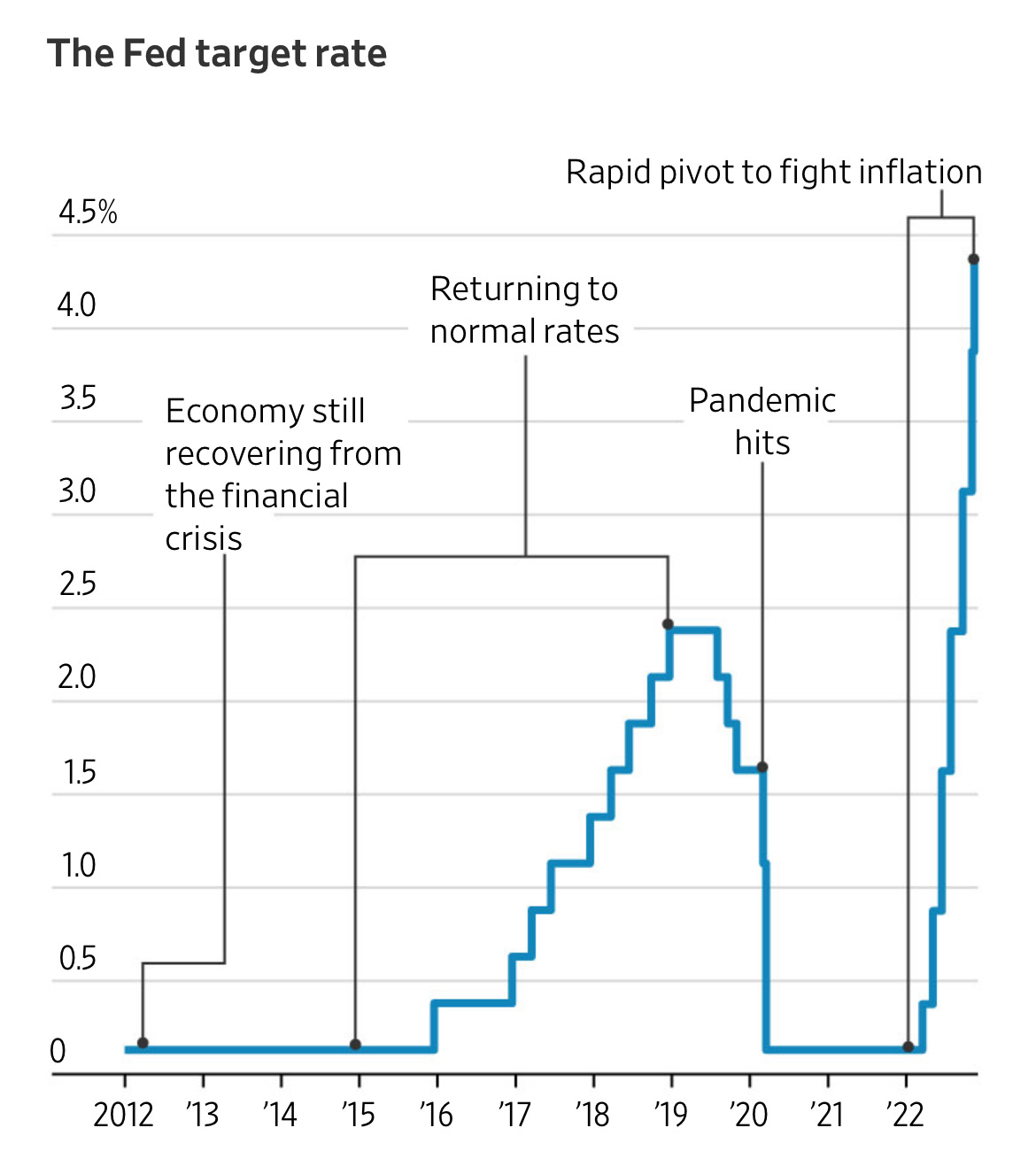

The end of the everything bubble. I was 28 when the 2008 housing crisis hit, unemployment jumped from 4.6% to nearly 10%, and the Fed lowered interest rates to stimulate the economy. Only in retrospect is it obvious that interest rates were kept too low for too long, creating the “everything bubble” of the last 5 years. We didn’t know what to do with so much money; it flowed into subsidized Uber rides, meme stocks, NFTs, the housing market, cryptocurrencies, and antique watches. Imagine where else that money could have been invested: childcare, infrastructure, pandemic preparedness, Americorps, child allowances, and free community college. Ezra Klein’s conversation with Rana Foroohar helped me realize how we missed a once-in-a-generation opportunity to expand and strengthen the working middle class. I have no idea where the economy will go from here. I can just as easily imagine the next decade of stagflation or a massive stock market rally fueled by productivity gains from AI & CRISPR. A lot of money will be made and lost depending on which way the economy goes. I’ll hedge my bets.

We thought that AI would displace accountants and lawyers, not writers, designers, and artists. AI hype and worry went mainstream over the past few months after the successive releases of Dall-E, ChatGPT, and Lensa. (f you haven’t played around with them yet, they are fun and magical — and the first-hand experience is more eye-opening than anything you could read.) I am firmly in the camp of This Changes Everything (at the scale of the printing press, steam engine, and internet). Noah Smith’s essay “Autocomplete for everything” gave me an optimistic framework for how we’ll likely work alongside AI over the next few years. He’s not being speculative; these tools are already in use by designers, programmers, and writers. Over the longer term, I am pessimistic. We’re too easy to fool, too eager to be manipulated by marketers and bad actors. I am slowly working on a longer essay about oral culture versus textual culture sparked by Daniel Herman’s piece in the Atlantic questioning the value of teaching writing composition in the age of AI. As a society and labor market, we are still trying to figure out the marketable skills of humans as AI outperforms us on an increasing number of tasks. For deeper dives into the implications of AI, I appreciated Tim Urban’s The Road to Superintelligence and Matt Yglesias’ skepticism that human intelligence is anything more than AI-like pattern recognition.

The return of, like, real war. I thought we were past the era of two nations going to war. I thought that the global economy was too integrated and national autonomy too established for any leader to survive the economic suicide of invading another country. And yet here we are. I assume that this will end poorly for Putin. Perhaps Ukraine will reclaim its lost territories, join the EU, and reaffirm Europe’s commitment to liberal democracy and rule of law. Then again, who would have guessed in 2001 that US troops would remain in Afghanistan for more than 20 years? Our fears of terrorist attacks seemingly disappeared without explanation and yet an AI-powered drone military conflict with China over Taiwan seems as likely as not. Hopefully, I’ll look back at that last sentence in 10 years and laugh at its exaggerated alarmism.

Rethinking live to work. Last year I read Dan Hamermesh’s newish book about how Americans spend our time — and how we tend to spend much more of it at the office and in front of the TV than people in other countries. He estimated how much income we would lose if Americans took on average four weeks of vacation each year instead of two. With two extra weeks of leisure, he calculated, GDP per capita would barely fall from $59,500 to $58,300. And yet, he pointed out, as people make more money, they tend to spend less time on leisure. Ours is a culture that has forgotten how to relax, make friends, and cultivate hobbies. Perhaps that is changing. 2022 was the year of quiet quitting. It was the year of Gen Zers making fun of Boomers for their obsession with productivity and professional status. Bookstores can now dedicate an entire shelf to books about “how to do nothing.” It was the year of Boomer managers (and Kim Kardashian) complaining that no one is willing to work anymore. I’m optimistic that more Americans, myself included, are discovering the soothing delight of detaching our self-worth from our job title and LinkedIn profile. I thought Ann Friedman did a good job covering the cultural shift this past year, especially for women, in her piece, What Comes After Ambition, as did Noreen Malone in The Age of Anti-Ambition.

Blockchain never found a use case, just an embezzlement scheme. During the first half of 2022, before AI took the limelight, the tech blogs were either hyping up or tearing down crypto and Web3. It’s worth revisiting Nilay Patel’s conversation with Chris Dixon and Naval’s two-part podcast with Vitalik to recall the fever pitch. Ethereum’s climate-friendly transition to “proof of stake” in September was supposed to be the most consequential technological breakthrough of the year, and yet it was hardly covered. Ironically, blockchain was supposed to embed trust into code; instead, it enabled the FTX embezzlement scandal and countless others. I assume there will be some future creative applications of Ethereum’s smart contracts, but I would also bet on Bitcoin losing most of its current value and that the Andreessen Horowitz VC firm will lose nearly all $2.2B of their 2021 crypto fund and most of the $4.5B of their 2022 crypto fund. (But who knows, maybe I’ll be laughably wrong; after all, I once thought that Google would fail as an advertising company that subsidizes a search engine. 🤷♂️)

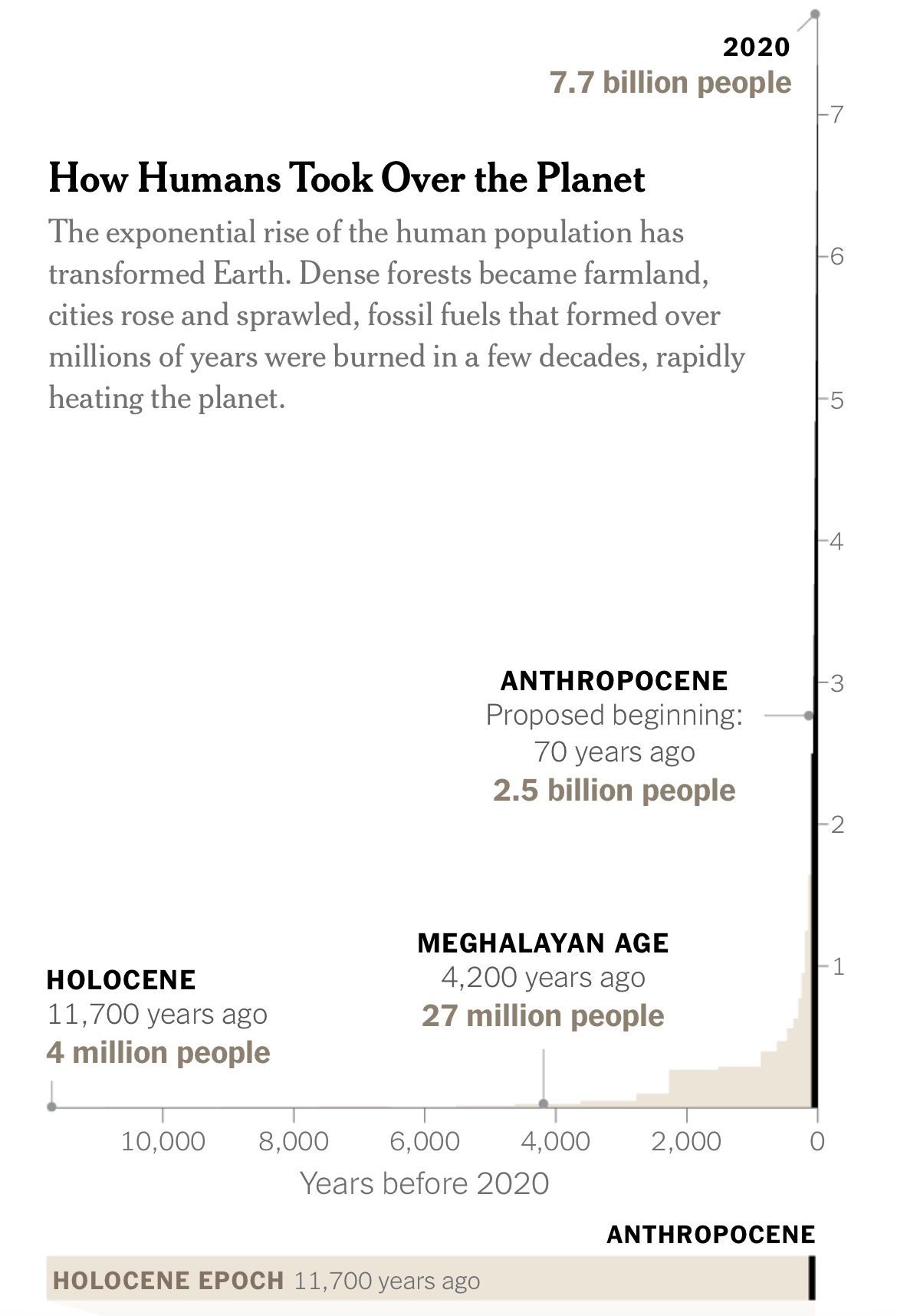

8 billion people. Too many or too few? Sometime in November, the global population reached 8 billion. That is eight times as many people that were alive just two centuries ago. Meanwhile, average life expectancy doubled since my grandmother was born in 1929. What a wild time to be alive! For the past 70 years, there was consensus that we needed to reduce the global population to live sustainably, but now I sense greater concern that our fertility rates are too low. “The West” (including Japan, Korea, and Taiwan) is below the fertility replacement rate and we’ll be dependent on Africa and South Asia to produce enough young workers to keep the global economy humming and to care for an aging population. As Bryan Walsh writes in an evenhanded piece on the population debate for Vox, “Trends may point to the last person in Japan dying in 2500, but Nigeria is on pace to pass the US with more than 400 million people by 2055. Next year, India will surpass China as the world’s most populous country. What will Japan look like with half its current population? What will Nigeria be like with twice its current population? And how many Nigerians will migrate to Japan? Can anything be done to convince people to have more kids in countries that have fallen below the replacement rate? And if not, will those countries openly welcome immigrants? Over the next 50 years, I expect that East Asia and the Gulf States will depend on South Asian immigrant labor while Europe fills with Africans and the US becomes more Latin. But the reverse could also be true. No one expected South Korea’s economy to grow so quickly after 1953; perhaps we’ll say the same thing about Nigeria, Mexico, and Bangladesh 50 years from now.

The decline of Twitter and Facebook, the rise of TikTok. In many ways, Luis and I were prescient when we speculated about the next 15 years of Twitter at the beginning of the year, including its focus on growing subscriptions. But we had no idea that Twitter would implode so spectacularly under Musk’s leadership. Just two years ago, Facebook and Twitter were the dominant platforms for spreading ideas and culture; now, suddenly both seem destined for obscurity. The six-part podcast series on Meta / Facebook by Land of the Giants helped me gain perspective on Facebook's 20-year rise and fall from a college directory to a desperate TikTok copycat and mostly empty VR playground. I am confident that we will always want a platform to 1) subscribe to updates from brands and individuals, and 2) comment in public about those updates. When something new does come along, hopefully, it won’t again nudge us to become our own worst versions. And maybe we really will see a rise of Luddite clubs on college campuses as the dominant counter-culture of the 2020s similar to the hippies of the 60s. I would love to see a 2025 “Luddite summer” in the spirit of the 1969 summer of love.

Free trade with friends. The Washington Consensus is no longer. Tariffs and subsidies are back and so too is industrial policy. Alexander Hamilton made a comeback in 2022 while Adam Smith suffered a setback. Most corporations are reworking their supply chains to become less dependent on China and other single points of failure. Tesla is about to open a new factory in northern Mexico while its China factory remains closed after a COVID outbreak. Will Vietnam, Mexico, and Brazil gain from China’s loss? Can the US truly become competitive in chip manufacturing? (The early signs don’t look good.) I am reminded of the Netflix documentary American Factory about a Chinese company that tried and failed to set up a factory in Ohio. How will we ever be able to compete with China’s insane work ethic, I remember thinking, especially at a time when Americans want to work less not more? Maybe all of these new investment and trade deals with Europe, Japan, Australia, and Korea will be the way. Maybe it’s good for overall innovation to have Cold War-like superpower competition with China. 🤷♂️

Moderates make a comeback. 2022 was the year that we finally got fed up with the far right and far left — and whoever was yelling the loudest. There was an anti-woke backlash, yes, but it happened at the same time as the anti-Trump backlash. The big orange bully has lost his grip and I’d be very surprised if he wins the 2024 election. We just may be on the path back toward political sanity. I enjoyed Malcolm Gladwell’s podcast about how the creators of Will and Grace ignored the loud criticism of their activist friends to create a moderate, mainstream TV show that transformed American attitudes about sexuality. Meanwhile, the leaderless social media movements (#MeToo, the Women’s March, Black Lives Matter, Indivisible, Sunrise, the March for Our Lives, The Dreamers) that got a social media turbo-boost during the pandemic have diminished, dissolved, or imploded. Micah Sifry asks what comes next for political engagement now that social platforms and social movements are both in decline? I thought that Jonathan Haidt’s essay blaming the political insanity of the past decade on the gamification of social media was persuasive. A major section of his essay is titled “It’s Going to Get Much Worse,” but 2022 gave me a glimmer of hope that the worst is behind us and that we’re on the cusp of a cultural shift toward an aesthetic of moderation and restraint that will move us past the last decade of outrage and toward a period of cultural and political renewal.

Actual climate change policy. I remember when some girls in middle school stopped using hair spray after they felt responsible for a hole in the ozone layer. All my life, climate change has sparked catastrophic alarmism but no real policies to do anything about it. This year, I sense that we’ve become less alarmist and more serious about investing in decarbonization and adaptation through the Inflation Reduction Act, the Methane Emissions Reduction Action Plan, and even the climate adaptation fund that came out of COP 27. Sure, these policies don’t meet the scale of the problem, but at least we’re finally doing something about it. And anyway, technological innovation enabled massive progress toward decarbonization even while governments have fumbled — no one expected solar to surpass coal so quickly. If the most alarmist predictions about temperature and severe weather come to pass, I assume some rogue actors will release reflective sulfur particles in the sky to cool the planet. In fact, they’ve already started.

The return of innovation. There is that famous Thiel quip from 2013: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Indeed, it was one groundbreaking tech innovation after the next between 2000 and 2010. And then it’s as if we ran out of ideas. Each new device and piece of software barely improved over the previous year’s model. Several books were published about our technological stagnation and cultural complacency. All of a sudden, those books now feel outdated. From AI to CRISPR to mRNA vaccines to new cancer treatments to electric airplanes to satellite internet to renewable energy to augmented reality and brain-computer interfaces, it seems that we’re on the verge of another decade of science fiction-like innovation. Noah Smith’s annual techno-optimism post has a good summary. He doesn’t even bring up Apple’s forthcoming AR headset and the wild implications of augmented reality. Driverless robotaxis are already out in force in China. A new brand will begin selling gene-edited produce in California supermarkets next month. Another California company has received FDA approval to sell lab-grown meat. As with all of the new technologies that were developed between 2000-2010, I assume that the innovations introduced in 2023 will have as many downsides as upsides — some of which we can guess today and others that are completely unpredictable. I expect that by 2040 when I am 60 years old, we will have abundant and nearly free energy and online connectivity. I assume that we’ll become accustomed to personalized virtual assistants who know us better than we know ourselves and that at least 20% of Americans will actively use some kind of brain-computer interface. And I fully expect fierce debates and conflicts over the regulation of AI and gene editing. Not quite Terminator and Gattaca, but frighteningly close.

The main questions I have for 52-year-old me reading this in 10 years are psychological and sociological. With all of the innovations and reasons for hope listed above, will Gallup’s annual World Happiness Report find that we are happier? Will the number of suicides and drug overdoses decline? Will we have more or fewer friends?

Paradoxically, I’m in favor of both technological innovation and equality, yet I’m not convinced that either makes us happier. When high-status communities lose status, they become resentful. When low-status communities gain status, they become more aware of all of the past injustices and discrimination — and so they too become more resentful. The result is a society that is more resentful and distrustful.

Meanwhile, each new technological innovation solves a minor inconvenience, stirring “a relentless drive to optimize all things for efficiency.” We have inherited a warming planet of 8 billion people in which we must continue our relentless drive to optimize (energy production, infrastructure, education, and healthcare) to live sustainably. At the same time, we’re ripe for a cultural transition that pushes back against the relentless drive to optimize for an existence of slowness, depth, and restraint.

Of course, Rousseau felt the same in 1762 and so too did Thoreau in 1854 when he wrote: “Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys, which distract our attention from serious things. They are but improved means to an unimproved end, an end which it was already but too easy to arrive at.”

It’s still too early to write the great American novel about this period; we are too close to it and we don’t know how or when it will end. Nor am I sure how it begins, but there is something about the 74 seconds of Donald and Melania Trump escorting Barack and Michelle Obama to the departing helicopter on inauguration day that strikes me as a powerful opening scene.

Looking back at Matt Yglesias’ predictions for 2021 and 2022, I am reminded of the future’s guaranteed uncertainty. It’s not just that I am sure to be wrong about much of what I wrote above, but there will be so much more that never occurred to me. I wouldn’t have it any other way. It’s the unpredictability of life that makes it so lovely.

I hope you have a most lovely new year,

David

Lullaby by Grace Ives. And you really are the Renaissance Man...but the athletic version. And what speed reading course did you enroll?

Nice reflections. Sorry to hear about the bike crash—hope your arm is okay.