When Languages Die, Part 3

Speaking dead languages with robots

Dear Friends,

As I researched this week’s newsletter, I had a moment of metaphysical rhapsody while reflecting on the emergence of grammatical language some 20,000 years ago and today’s rapid advance of AI reasoning by detecting patterns in our externalized thoughts. (Like my very own, right now!)

It made me wonder: Is intelligence the inevitable result of language? And did language emerge as a series of grunts while dancing around the fire? Big questions, I know.

This is the final installment of the series on endangered languages and artificial intelligence. In part one, I shared my experience at a gathering of indigenous language activists and technologists. Part two explored the politics of multilingualism and how nations often seek unity through a common language. Now, for part three, let’s address the question I’ve been teasing all along: What do we lose when we lose a language?

Could we talk to our distant ancestors?

Probably not. Pretty sure we don’t even know what language they spoke.

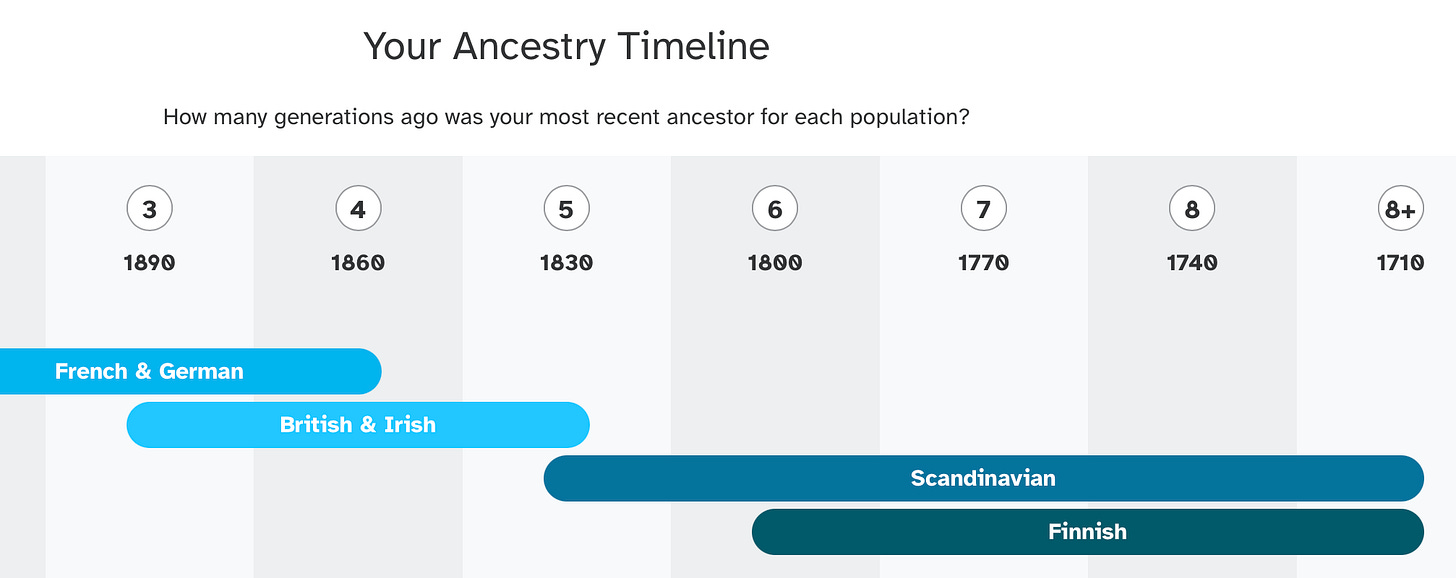

My great-great-great-great grandma, Flora Knudson, was born in Norway in 1843 and eventually migrated to Wisconsin where she married Pratt Taylor, the descendant of early Pilgrims.1 Unfortunately, Ancestry.com doesn’t provide me with any information about Flora Knudson’s parents, so I can only guess whether spoke Dano-Norwegian or a regional dialect.2 And does it matter? I’m only 6% Norwegian, a European mutt with ancestors scattered across the continent. Even if I discovered which dialect Flora spoke, would I dedicate time to learn it? Similarly, will future descendants of today’s endangered languages learn the extinct languages of their ancestors? Would doing so change them?

Do we take on different personas in different languages?

Iris and I tend to discuss our to-dos in English and our emotions in Spanish. True to stereotype, there is something about English that suits planning and something about Spanish that connects to emotion. A 2004 study of bilinguals in the US and Mexico found that Spanish responses emphasized family values, whereas the English versions focused on personal success.3

But what about Mexico’s bilingual population who speak both Spanish and an indigenous language? Do their personas change as well? Surprisingly, I couldn’t find any published research, but I did have a fascinating conversation with Idelfonso Sánchez of Hablemos Purepecha, a language preservation initiative in Michoacán.

I asked Idelfonso about the most difficult part of his job. “Getting people to care,” he said. “Young people today don’t want to learn the language of their grandparents. They have phones, they speak Spanish, they want to move to the city. Or to your country.”4

I asked if Idelfonso takes on a different persona when speaking P’urepecha versus Spanish. After a thoughtful pause, he replied that while speaking P’urepecha he’s more deferential to his elders and duty-bound to his community. In Spanish, he feels more entrepreneurial.

Idelfonso’s latest project encourages grandparents to speak P’urepecha to their grandchildren, while encouraging school-aged children to take more interest in the lives and language of their grandparents. Still, it’s an uphill battle, and he worries the language could disappear within a couple of generations.

I’m curious to see what becomes of Purépecha—and other endangered languages—when I reopen my Time Capsule in 20 years.

Speaking dead languages with robots

Last week, Microsoft announced that its Teams platform product will gain instant speech-to-speech interpretation for nine languages, expanding to 31. Google followed with live translation for customer service call centers, and French telecom Orange announced a partnership with Meta and OpenAI to build AI models for African languages starting with Wolof and Pulaar.

It seems inevitable that in twenty years, our AirPod-like devices will offer real-time translation for any language, including languages that haven’t been spoken for centuries.5 (With a decent internet connection, this is pretty much true today.) The devices will even provide cultural context for untranslatable concepts.6 So if we can converse in any language, including those of our ancestors, what is truly lost when a language goes extinct?

Culture and language as communal bond versus identity expression

Culture and language used to connect us to our local community; increasingly they are aspects of our identity that we express for others. Young people interested in Purépecha today are likely more motivated by a desire to explore their ethnic identity in California than by a need to communicate with family in Michoacán7

I thought about this difference while listening to the Pretendians podcast, which explores cases of “indigenous identity fraud.” As far as I can tell, neither of the show’s hosts speak the languages of their tribes, and yet they are passionately focused on sharing stories of ethnic fraud to a mostly white audience.8

Their podcast strikes me as a signpost for the future of endangered languages and ethnic identity. Yes, endangered languages may disappear from their local communities, but they will live on in AI chatbots and in the social media profiles of descendants seeking unique cultural markers.9

And so in a way, the languages will survive. Our descendants, like us and our ancestors, will strive to assimilate into dominant cultures while emphasizing their uniqueness.

I’m glad to have finished the series.10 If you’ve made it this far, I appreciate your persistence and would love to hear your reflections — either via email, or in the comments below.

Yours,

David

And then she later re-married Charles Taylor. Were they brothers? Did she marry Charles after Pratt passed away? It’s all unclear.

It wasn’t until the 1960s — more than 100 years after Flora emigrated — that Norway’s government formed the Language Peace Committee to standardize Norweigan and “defuse the conflict about language in Norway to build an atmosphere of mutual respect.” Karl Ove Knausgaard writes in My Struggle about his strong sense of Norwegian identity when living in Sweden compared to his sense of being an outsider in his own country when he can’t properly speak the dialect in northern Norway. I relate; I feel very American in Mexico, but not at all in Texas.

Researchers found similar results between bilingual speakers of Chinese and English.

Indeed, if you’ve ever driven to the Coachella music festival, you’ve likely passed by Purepecha descendents working the farms.

Ross Perlin makes an unconvincing argument that language only has meaning with agency, and therefore any AI-generated language is not actually language.

For instance, there is no direct translation for “compromise” in Spanish. “Compromiso” means commitment. You could say “concesión” as in concession or “acuerdo” as an agreement, but there’s nothing to capture the mutual, negotiated concession of a compromise.

Indeed, most of the commenters on Hablemos Purépecha YouTube videos are based in the US.

Co-host Angel Ellis is one of 100,000 members of the Muscogee Nation, but only about 400 of them still speak their tribal language. Her co-host, Robert Jago, a member of the Kwantlen First Nation & Nooksack tribe, is writing a book (in English) about his family heritage. The Nooksack language went extinct in 1988 with the death of its last living speaker, Sindick Jimmy. Hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, the language of the Kwantlen, is now spoken by fewer than 100 people. It’s natural, I guess, that Ellis and Jago are more interested in exposing Pretendians to a white, English-speaking audience than learning the language of their ancestors.

Will Buckingam writes how young Taiwanese of Chinese ancestry are learning the indigenous language, Tâi-gí, to distance their identity from mainland China. Fascinating. It’s like an 18th century pilgrim learning Navajo to diminish her Britishness!

When I read back on this in 20 years, I’d like to check in on the following:

Of the 6,000 - 7,000 active languages spoken today, how many survive over the next 20 years? How many are fluently spoken by the leading AI model? Also, have we resolved the contentious debate between Steven Pinker &

on one side and Noam Chomsky on the other about whether language evolved gradually in humans, or all at once?What’s the career path of Elizabeth Esteban-Hernandez, the descendent of P’urapecha immigrants to the Coachella Valley who received a full-ride scholarship to Harvard?

What about León Axuni, a P’urepecha entrepreneur who studied in the UK and returned to Mexico to give a candid TEDx talk about his attempts to integrate his P’urepecha, Mexican, and British identities?

Lovely series, David! As someone who cares deeply about language and their roles in cultural connectivity, I really appreciate the insights you put together.

I recently read something about how the US Census Bureau is looking to minimize the number of races we identify as, although it's already quite concise.. maybe East Asians and South Asians will eventually become just 'Asians' as a result of their efforts. But I predict that the same thing will happen to languages, as you mentioned. The assimilation generations will lead to the dominant languages absorbing all the smaller dialects. Would be interesting to revisit in 100 years.