When Languages Die, Part 2

An end to 50 years of multiculturalism and the rise of ethnolinguistic nationalism?

Dear friends,

Imagine that you’re one of the last 500 speakers of a language. Your parents spoke the language. Their parents spoke the same language, and so on for thousands of years. But now, within a generation or two, it is likely to disappear forever.

My favorite writers zoom in on a personal experience, zoom out to suggest a theory about How The World Works, and then zoom back in with a story to illustrate the framework and speculate about the future. That’s my aim with this week’s series about what we lose when we lose a language in the age of AI.

On Thursday, I described putting that very question to a conference of indigenous language activists. I’ll share their responses soon. But for today, if you’ll indulge me, let’s take a short detour to zoom out and explore the post-colonial periods of modernization (1940-1970), when national integration was the priority, and multiculturalism (1970-2022), when we celebrated our differences.

Have we entered a new period? Consider the ironies:

On U.S. college campuses, progressive students advocate for indigenous land reclamation projects, while exit polls suggest 65% of actual Native Americans voted for Trump.

In Mexico, a Jewish climate scientist received an indigenous blessing at her presidential inauguration.1 And yet, beyond the political symbolism, the government’s approach to indigenous policy marks a return to modernization theory — connecting indigenous villages to industrial parks and tourism developments through massive infrastructure investments.2

What does any of this have to do with the disappearance of indigenous languages? Across the world, voters are turning against immigration, globalization, and multiculturalism — and toward tariffs and ethnolinguistic nationalism. For instance, one of Trump’s most popular campaign lines was that every American should speak English. The monolingual advocacy group ProEnglish hopes that Trump and a Republican Congress will pass the English Language Unity Act to limit government communication to English, defund bilingual education, and tighten the enforcement of English fluency for citizenship.

In Mexico, the previous president attempted to remove the office for indigenous education from the Department of Education and place it in a new, underfunded Institute for Indigenous Affairs. Similarly, a new university for indigenous languages in Mexico City has yet to receive any promised funding.3

The European Union — amidst the rise of the anti-immigrant, nationalist right — declined to recognize Catalan, Basque, and Galician as official languages. In France, students are prohibited from speaking regional dialects like Breton or Alsatian in school.

In India, Narendra Modi is pushing for Hindi to become the dominant language while diluting affirmative action policies designed to benefit marginalized groups.

As immigration, globalization, and technological change increase, so does a reactionary push for more border enforcement, tariffs, and cultural assimilation.

Should a Country Speak a Single Language?

Like Italy, Tanzania, and China before it, India’s government has long sought to unite the country around a common language.4 There are various advantages to a common language, including economic efficiency, a unified educational curriculum, and a shared sense of national identity. Research shows that multinational firms are less productive when their workers speak different languages, and the same likely holds true for nations.

Mexican intellectuals in the 1950s agreed. The archeologist Alfonso Caso, the first director of Mexico’s National Indigenous Institute, argued that indigenous communities were excluded from the benefits of the so-called “Mexican Miracle” of industrial development and the emergence of a middle class. Caso’s institute prioritized two initiatives: agrarian reforms to help indigenous farmers earn money and educational reform to teach Spanish and integrate indigenous people into the industrial economy.

Caso was influenced by modernization theory. He believed indigenous Mexicans wouldn’t benefit from liberal democracy unless they spoke the national language and participated in its economy. By his death in 1970, however, modernization theory had given way to multiculturalism.5 Leftist, post-modern scholars joined forces with indigenous activists to protest cultural hegemony and the linguistic domination of colonial languages. The postmodern period continued through the 1990s with anti-globalization protests and the glorification of the Zapatistas.

By the time Obama was elected in 2008, it seemed like we found a healthy balance between multiculturalism, globalization, and national pride. Obama reminded us to respect our differences while taking pride in what unites us. China was still a source of cheap electronics, not yet a threat to the middle class, democracy, or the race to build artificial general intelligence. Both Democrats and Republicans supported foreign trade.

The Ethnolinguistic Nationalist Turn

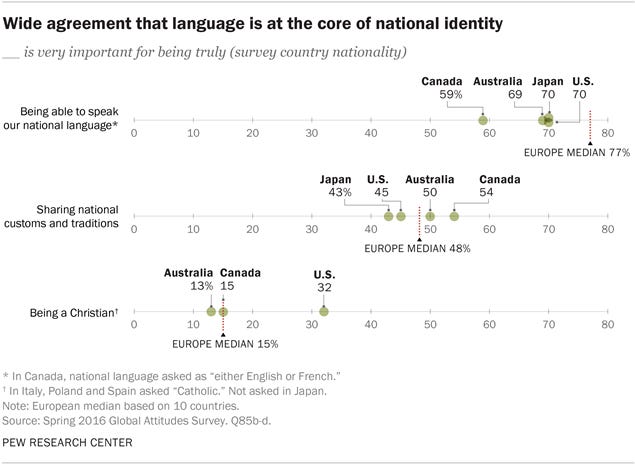

But what about today? Support for foreign trade has declined. Support for immigration has nosedived, especially among Republicans. And a 2016 survey of more than 14,000 respondents in 14 countries found that speaking the dominant language is the most important aspect of national identity.

It was just two years ago that American schools segmented their students into racial affinity groups and urban progressives appended indigenous land acknowledgements to their social media bios. Now, those acknowledgements have largely disappeared, and Boston Public Schools faces a federal investigation over race-based affinity groups. The 50-year stretch of multiculturalism is in retreat amidst calls for patriotism, cultural assimilation, and stricter immigration enforcement.6 If anything, we seem to be re-entering a new period of modernization.

None of these political trends bode well for the preservation and flourishing of indigenous languages — not in the U.S., Mexico, India, or just about anywhere else.

In 1930, 16% of Mexicans spoke an indigenous language. By 2015, that number had fallen to 6.6%. What can we expect by 2050? And how are indigenous language activists responding to these political headwinds? Will AI help or hinder their efforts?

Stay tuned for the final newsletter in the series. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts and reactions — either in the comments below or by email.

Yours,

David

She also replaced a statue of Columbus for a monument of an indigenous woman, and changed the national emblem to a young woman in indigenous clothes

To clarify, I’m supportive of these economic development projects and supportive of funding indigenous language education.

Roughly 6% of Mexicans speak an indigenous language compared to 1% of Americans. In both Mexico and the U.S., the vast majority of indigenous language speakers reside in just a handful of states.

“Mahatma Gandhi, fearing India wouldn’t hold without a national language, proposed that it be Hindustani, which encompasses both Hindi and the very similar Urdu of many Indian Muslims.” The Indian government recognizes 22 official languages. The 2011 Census of India identified 270 mother tongues with 10,000 or more speakers each. Ethnologue lists 424 living indigenous languages.

And the Mexican Miracle gave way to economic mismanagement.

To be sure, I am a fan of immigration, diversity, and multiculturalism … but I also support democracy and recognize when my views are not in the majority. I’m hoping that they will be soon, that we’ll return to the Obama-era idealism of diversity and unity.

As always, very interesting David! This might not be an angle you’re interested in, but at the end of the piece I was wondering about why multiculturalism has had a backlash. From a US perspective, is it just that it was done poorly? I think about land acknowledgements and how they can feel very accusatory (“we’re on the unceded grounds of … “) versus celebratory (“ we recognize the original stewards of this land and honor their legacy…”). Or is multiculturalism always going to come with some amount of feelings of exclusion? (Which is my hypothesis for the backlash)