Dear Friends,

I, too, have big thoughts about today’s affirmative action ruling by the Supreme Court, but so does everyone else — and anyway, my thinking hasn’t really changed since I wrote about it last November:

I value diversity and I value fairness. I’d like to live in a society that optimizes for both, though I realize they are sometimes in tension. I can be easily convinced that we need affirmative action to increase diversity. I am also swayed by arguments —like this one by Asra Q. Nomani — that college admissions should be based on merit, not skin color. Most of all, I don’t think that elite university admissions should be, in the words of Justice Elena Kagan, the “pipelines to leadership in our society.”

Iris and I had a fun joint birthday weekend in the Trinity Alps, including a majestic hike along Canyon Creek — highly recommended! Now I’m back in the office for a week of paperwork and meetings to plan for future meetings. 🤷♂️ On Friday, I’m off to Emigrant Wilderness with two dear friends for some more backpacking, so you’ll get a deserved break from this surprisingly consistent newsletter. Before I leave, here’s the fourth and final installment of the “Millennial Midlife Transition” series.1 If you’ve stuck with it, I thank you. I know that I’m not the only one going through this right now … and it has sparked some meaningful conversations with friends, old and new. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts if any of it resonates; you can reply directly to this email or leave a comment below.

Middle age is a period of both disappointment and liberation. It is when we realize paradoxically that 1) we won’t attain the dreams of our youth and 2) we don’t need to chase the expectations of our parents. Arthur Brooks observes another paradox: The very things that made us successful between 25-45 — striving and standing out — will make us unhappy between 45 and 65 if we don’t adjust.

Hmmm, maybe I should stop hiding behind the pronoun “we,” and admit that I had little awareness of the unconscious forces that shaped my personality, relationships, and career.2 But now — after a few years of therapy, introspection, and a global pandemic — I have a clearer idea of what genuinely motivates me. So, what do I do with this newfound self-awareness? How do I craft a second half of life built not on the unconscious forces I inherited but on the conscious choices that bring me joy, serenity, and meaning? That is the topic of this week’s newsletter, the final in the series.

But first, why did I start this series?

The most obvious answer is that I’m on the cusp of major life changes, including a new career, country, and the still-pending decision of whether or not to have children. Beneath all of these decisions there are fundamental questions: Are we doing this because we feel we ought to? Are we reacting to fear or social pressure? Or is this our true desire of what we want most out of life? And also: How do we balance our own desires with the expectations of others? (More on that last point in the next section.)

A less obvious answer is that I was unexpectedly affected by a British documentary 60 years in the making called The Up Series. In 1964, Michael Apted began filming the lives of 10 boys and four girls from different social backgrounds in London. Every seven years, he revisited them when they were 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, 56, and — most recently, in 2019, 63 years old.

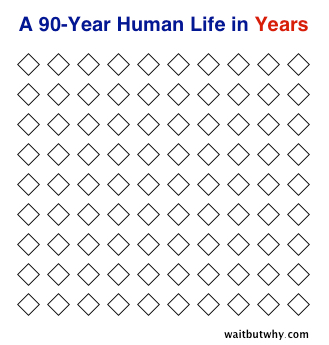

The 60-year series is a reminder of how much of our lives are shaped by the class, social expectations, and personalities we are born into. But it also shows how the participants’ lives can go in radically different directions based on the decisions they make in the seven years that pass between each episode. I was hit hard by the sixth episode when they are 42 years old. Holy shit, I realized, that’s me. I, too, am halfway through the story. I could see how their decisions at 42 would play out in future episodes when they are 49, 56, 63, and 70. It inspired me to pay more attention to my own decisions and priorities.

The fear of being normal

In my youth, I sought meaning through influence. I wasn’t sure how that influence would take shape: Maybe I would write a novel read by millions of people. Maybe I would produce journalism that created the first draft of history. Maybe I would change policy that would affect the lives of millions.

To have influence, I needed power. And to get power, I needed ambition and prestige. I worked relentlessly. I didn’t exactly ignore my friends or family or health, but when I thought about my role and purpose on this planet, it was to affect as many people as possible by maximizing my influence. In the words of Arthur Brooks, I wanted to be “special:”

What workaholics truly crave isn’t work per se; it is success. They kill themselves working for money, power, and prestige because these are forms of approval, applause, and compliments. Why? For some I have met, the thrill of success, albeit momentary, blots out the blackness of “normal” life.

Something is clearly wrong when the idea of being “normal” induces enough panic to make someone neglect the people they love in favor of the possible admiration of strangers.

I eventually discovered that my drive to be special and influential distanced me from the very people I wanted close to my heart. Nobody wants to be influenced; we want to be understood and to have fun.

Reinvention and individualism

I am in the midst of a personal reinvention, as I’ll describe in the next section. I am also asking myself: What are the conditions that allow for personal reinvention? To what degree should I dismiss the expectations of others as I seek my own happiness and freedom?

Those are the same questions that John Stuart Mill was asking in the 1850s as he drafted On Liberty — a foundational text of Liberalism. Mill did not have a happy childhood and when he wrote the following about freedom, he may have been thinking about his father:

The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it.

Mill did not grow up “pursuing his own good in his own way.” His dad was an extreme “tiger parent” who taught his son: “Greek at age three, reading Plato by seven; Latin at eight, Newton’s Principia at age eleven; the teenage years devoted to logic, political economy, law, and psychology; then Bentham and philosophy at fifteen.”

Eventually, Mill suffered a midlife crisis, as described by the philosopher Keiran Setiya. Mill was raised to believe that the only path to happiness was by focusing on the improvement of mankind and the happiness of others. He was so distant from his own desires that he didn’t know what gave him pleasure.3

After his crisis, Mill reinvented himself. He found love and poetry and freed himself from the tyrannical expectations of his father. Unsurprisingly, he also became obsessed with the concepts of liberty and freedom from authority (his dad, but also the government) to peacefully pursue one’s own path to happiness.

Today we both celebrate and question the individualism we inherited from Mill and other Enlightenment thinkers — the unprecedented freedom to pursue our own path to happiness. For most of us in North America, Europe, and East Asia, we are now free from “the tyranny of the cousins” — the stream of criticism from extended family if we don’t work in the family business, or practice their same faith, or participate in the same weekly rituals. On the one hand, we are free to choose where we live, our profession, spouse, faith, friends, politics, and hobbies. On the other hand, freedom from tyrannical cousins has left us feeling isolated without shared purpose or meaning. In a discussion about the future of tribalism, Sean Illing confessed his growing resentment that he was raised without the opportunity to be part of a tribe, even if it came at the cost of less personal freedom.

I am mindful that my midlife reinvention is made possible by individualism and freedom from the expectations of others. At the same time, I know that too much individualism and freedom will get in the way of a meaningful and happy second half of life. So how will I balance my individual desires with my desire for community?

A different kind of ambitious

It’s so cliché: I thought I wanted success when in fact I wanted mutual love. I thought I wanted influence when I really wanted collaboration. I thought I needed to be special and was afraid of being normal.

I don’t mean to pathologize all success and ambition. I don’t think that every successful, ambitious person is acting out psychologically to live up to the conditional love of their parents from decades ago.4 Sometimes we are genuinely motivated by an implicit desire to contribute to something bigger than ourselves … and that’s just the kind of project I’d love to get involved in.

Few of us grew up with parents who loved us for who we are rather than what we achieved — and that can have its advantages.5 At 43, I am at peace with my ambition and striving, but much like the writer Rainesford Stauffer, I am rethinking how I use it. She observes:

I'm still ambitious about work, but in a more meaningful, sustainable way, with a better sense of how I contribute rather than just what I produce. To me, if we really break it down, a lot of ambition is where we put dedication, care, and passion. That could be how we're of service to other people, how we show up as a friend, and how we invest in what we love, whether it's a community or a hobby. I think contributing, healing, and caring are ambitious. I've found there is so much for me to be ambitious about, way beyond the context of accomplishment.

Come help me build my collective, collaborative cabin

So what do I want to build during the second half of my life? Quite literally, a cabin. I have dreamed of building a cabin my entire life since I was young.

There is a trope of the middle-aged man in Carhartt pants who decides to build “a place of his own” of Instagrammable perfection with his two hands. That is the premise of Michael Pollan’s book “A Place of My Own,” which I admit I enjoyed. But it’s not how I want to build our cabin.

Beyond a place for rest and creativity and communion with nature, the cabin is a metaphor for some general changes I want to make as I enter the second half of life. I want to more actively seek out the help and ideas of others. (Are you interested in helping build? Plant a vegetable garden? A DIY coffee roaster?) I want to create more collective rituals in my life — perhaps a week-long writer’s workshop to share feedback on drafts or maybe something more psychedelic? I want to enjoy the process of slowly building and improving the cabin without obsessing over the finished product. Most of all, I want unhurried creative partnership. At 43, I certainly don’t have it all figured out — and that feels great.

🧰 A useful tool

Last year, I was going to spend $350 on a satellite messenger from Garmin and a $15 monthly subscription to share my location with my wife when I’m out in the mountains.6 Then, Apple announced the same basic functionality for free on the new iPhone 14 and this past weekend in the Trinity Alps was my first chance to try it out. It was seamless! You can update your location every 15 minutes for free and it will appear on the phone of anyone who has access to your location in the Find My app. (The person viewing your location via satellite needs to have iOS 16.1 or later on their phone.)

Beyond sharing your location with loved ones, if you get into trouble you can use the free SOS satellite feature, which brought help to Juana Reyes this past weekend when she broke her ankle on a hike.

👏 Kudos

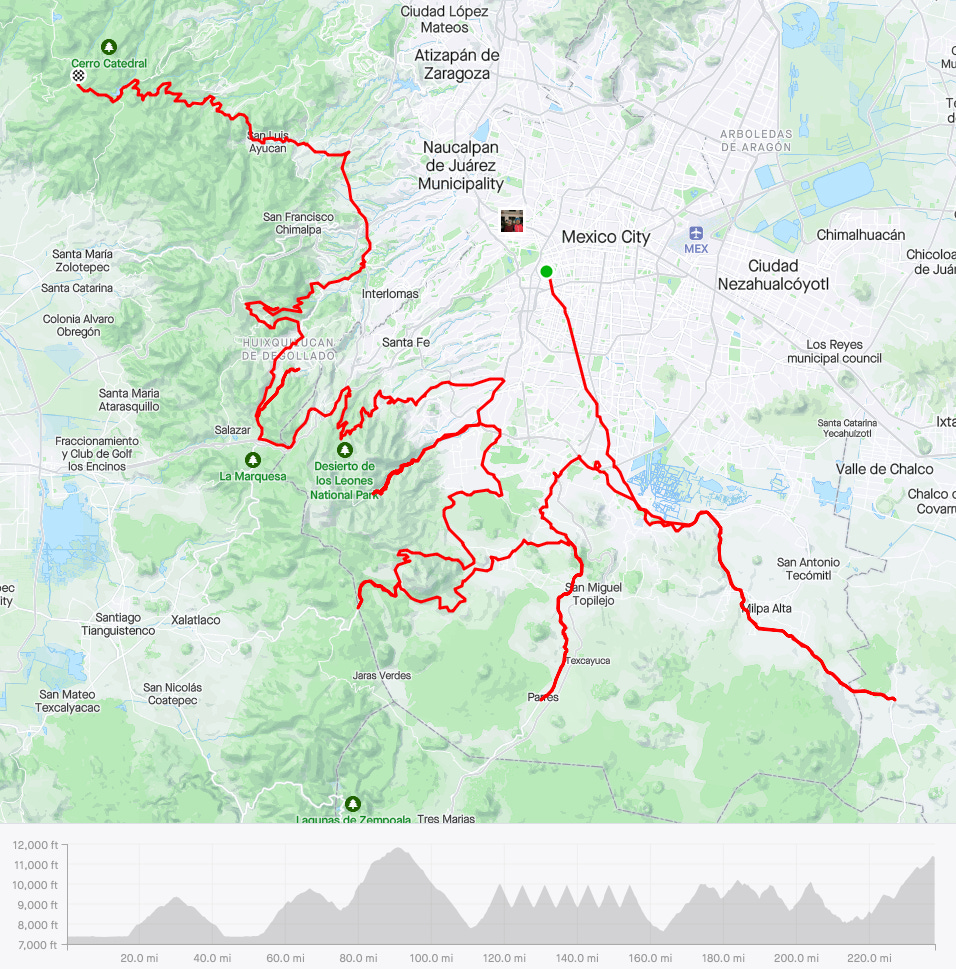

Big kudos to Sebastian Miranda who climbed all of Mexico City’s iconic climbs in a single day: 28,300 feet of climbing over 238 miles in just under 22 hours. Wow, I can’t even imagine.

🚵 Tour de France Fantasy

I love how many friends are getting into this year’s Tour de France after watching the (excellent) documentary series on Netflix. I was terrible at last year’s fantasy pool, but this year I have read “How to Not Suck at Fantasy Tour de France” and I’m hoping to improve. If you’re interested in playing along, here’s the link. (I’ll be in the mountains for the first three stages, so you’re sure to have a head start.) Here’s my roster for stage 1:

Have a great week and for those in the US, a happy 4th of July,

David

The experience of midlife for our generation is incomparable with how our parents experienced it — that was the topic of part one of the series. But some parts of the midlife transition do stay the same, like the changes to our bodies and faces and physical abilities —that was part two. In part three, I ask whether the 40-something adult we imagined that we’d become when we were young is somehow more authentic than the person we ended up becoming after making the inevitable compromises of Real Life.

Why, for instance, was I a people-pleaser while also having a chip on my shoulder? Why would I occasionally sulk instead of just stating what was bothering me? How could I be so allergic to narcissism while also wanting to be seen by others? I had all of the answers, as it turned out; I just needed a few years of therapy to articulate them.

A young John Stuart Mill would have surely attended an Effective Altruism conference.

has a nice description of how Mill eventually attained a more balanced life that includes pragmatism and poetry.But I do wonder if it’s the case 95% of the time.

When I was stuck in a flood on the John Muir Trail last year, a couple of people were airlifted to safety thanks to their Garmin satellite devices.

I’m really curious about the Up series and if there were any decisions you analyzed. Did anything surprise you? At 42, did someone change careers or leave a place or do something that dramatically changed course of the next 30 years for them?