Dear Friends,

If there has been a unifying theme to this newsletter since I started out ten months ago, it has been to look back at changes over the past 25 years since I graduated from high school to imagine the next 25 years until I retire. There is a term for this stretch of life between 40 and 60, of course, and my fellow “elder millennials” are getting our first taste of it.

But I don’t feel middle age. I relate entirely to Jennifer Senior’s essay in The Atlantic, which describes why, after a certain point, “you always feel 20 percent younger than your actual age.” Though 53 in biological years, Senior says she is suspended at 36 in her head. But she didn’t always feel this way:

I felt 40 at 22, when I barely went to bars; I felt 40 at 25, when I started accumulating noncollege friends and realized I was partial to older people’s company. And when I turned 40, I was genuinely relieved, as if I’d finally achieved some kind of cosmic internal-external temporal alignment. But over time, I rolled backward.

That’s me! I was an old soul in a young body with mostly older friends … until the past few years when I started to feel younger, look older, and hang out with mostly younger friends.1 In my head, I’m in my mid-30s. But then occasionally, I am startled to discover that the middle-aged, graying man staring back at me is my own reflection.

This is the first of a three-part newsletter about the Millennial midlife transition.2 First, I want to look at what has changed about society in how Millennials experience midlife today compared to how our parents, the Boomers, experienced it 20-30 years ago. Part two focuses on how I have experienced the physical changes of midlife and my struggles to get used to a body that neither looks nor reacts the way I expect it to. Finally, in part three I pull out my vulnerability pen to share some reflections about how I am changing as I settle into midlife with the hope that you might relate to some of it, and maybe it will even prompt a conversation.

The myth of the broke millennial

It’s boom times for cultural commentary on Millennial middle age.3 Rising above the din, it was Jessica Grose’s essay for the New York Times that went viral: “Millennials are hitting middle age — and it doesn’t look like what we were promised.” If there was a “promise” about Millennial middle age that didn’t come to fruition, Grose blames the bestseller from 2000, “Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation”:

What the authors could not foresee was that there wouldn’t be just one crisis. There would be a series of cascading crises, starting the year after their book was published. There was the fallout from the dot-com bubble burst; then there was Sept. 11, followed by the Great Recession in 2008; then came the political chaos of increasing polarization, the specter of climate change, and finally, the Covid pandemic.

That is quite the 20-year stretch! No wonder

and were inspired to write bestsellers at the end of 2020 to explain, respectively, “How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation” and “How My Generation Got Left Behind.” You know the story even if you haven’t read the books:Entering the job market during the 2007-08 financial crisis, millennials are the only generation to have a lower salary than their parents.

Unlike previous generations, Millennials are too poor to buy a house.

Strapped with student debt and high rents, Millennials aren’t able to save for retirement or build wealth

Millennials don’t have enough money to have children

But do these claims about Millennial misfortune truly hold up? And was 2000-2020 really worse than 1980-2000? In last month’s Atlantic, Jean Twenge debunks each of the above four bullets:

In fact, “by 2019, households headed by Millennials were making considerably more money than those headed by the Silent Generation, Baby Boomers, and Generation X at the same age, after adjusting for inflation.”

“Millennials’ homeownership rates in 2020 were only slightly behind Boomers’ and Gen Xers’ at the same age: 50 percent of Boomers owned their own home as 25-to-39-year-olds, compared with 48 percent of Millennials, hardly a difference deserving of headlines or social-media memes.”

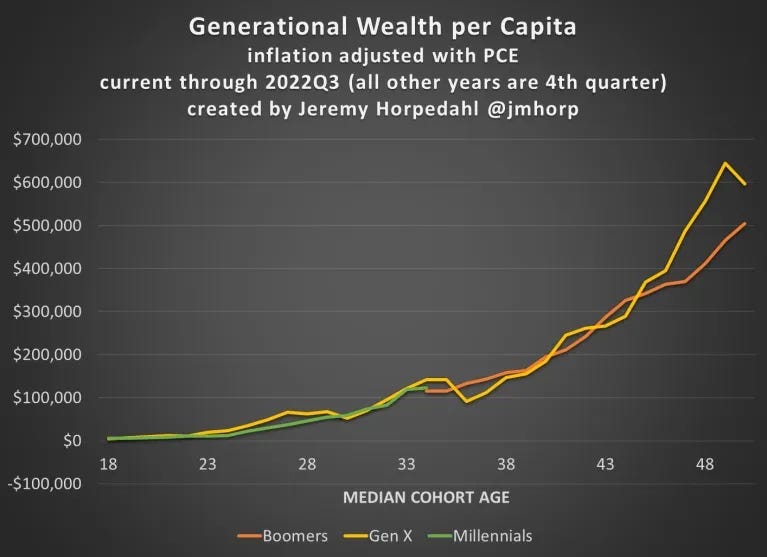

Average Millennial real wealth by age tracks Boomers and Gen X even though they are entering the workplace later.

And while it is true that the cost of raising children has increased for millennials compared to previous generations, the declining cost of electronics, cars, and clothes has more than made up for the difference.

So why do millennials feel so poor (and angry) when they are better off financially than any previous generation? Twenge blames mainstream media, social media, and unrealistic expectations. I think she’s right:

Before social media, the only rich individuals most people encountered were from the particularly well-off families in their town. Now the rich (or at least those who appear to be rich) fill our feeds and our screens, providing a skewed view of how other Americans live … Meanwhile, negativity in the news—which, studies show, has become much more pronounced in recent years—has colored perceptions of generational progress. A seemingly endless array of articles and news segments have repeated the idea that Millennials have gotten the shaft economically, an idea that social media amplifies further.

This constant drizzle of grievance and disappointment falls daily on a generation that carried extraordinarily high expectations into adulthood—more than half of Millennials, for example, expected to earn a graduate degree. In a 2011 survey, Millennial teens believed they would make, on average, $150,000 once they settled into their career—more than four times as much as the median income that year.

This is 40

Twenge’s correction of the dominant cultural narrative of Millennial misfortune is important because the stories we tell ourselves are informed by what we see in the media at least as much as what we experience in our own lives.4

So if most Millennials aren’t too poor to experience the “luxury” of a midlife crisis, as Grose suggested in her viral NYTimes piece, then what has changed about how Millennials experience the midlife transition compared to our Boomer parents? For one, it has diverged into thousands of different kinds of midlife experiences.

After their rebellious Summer of Love, most Boomers still followed their parents’ life trajectory (and parental expectations). They got married, had children, and entered the workplace in their 20s. They bought homes and began investing in the stock market. Throughout their late 30s and early 40s, they rode the wave of the unprecedented 1990s economic boom. When I graduated from high school in 1998 and left the house, my parents were 43 years old — my age now. At 43, my parents found themselves with more money than they could have imagined in their 20s, but they didn’t find happiness or meaning. They struggled to cultivate community or nurture hobbies. A few years later they divorced, my mother chasing adventure in Indonesia and my dad quickly remarrying and delving deeper into his work.

Most Boomers could relate to Gail Sheehy’s description of the midlife crisis, which she popularized in her best-selling 1974 book “Predictable Crises of Adulthood.”5 According to Sheehy, most of us spend our 20s and 30s shaping our character to fit the life course we stumbled upon: our marriage, our career, our neighborhood, our familial expectations. Then in our 40s, we can no longer suppress the incongruence between our character and our life circumstance. We feel out of place. As the recent series Fleishman Is in Trouble and Beef portray, some Millennials can still experience the classic midlife crisis in their early-40s. But most Millennials structured our 20s and 30s differently from Sheey’s description of our Boomer parents.

We spent our 20s meandering. We dated more and married later. We worked more jobs for shorter durations. We had fewer children later in life. We traveled more. We have access to all the world’s information. We are just a click away from updates about nearly every person we’ve ever met. We have grown up with the expectation that we ought to express rather than suppress our emotions. We confront rather than protect long-held familial secrets.

It’s not just that the midlife transition looks so different for each of us, but also, it occurs at a different point in life for each person.6 I think that I’m going through my midlife transition right now. But it could be that Iris and I choose to have children next year and I end up thinking that my true midlife transition takes place in my early 60s and I end up living until 110. 🤷♂️

Whatever I choose to ultimately call it, I know that I’m in the midst of a major life transition. I don’t just mean a new job and a new place to live later this year … I mean a re-examination of what motivates me, what gives me meaning, which decisions are mine to make, and how I want to spend the second half of my life. But that is for parts two and three.

🧰 A useful tool: Apple Card & Step

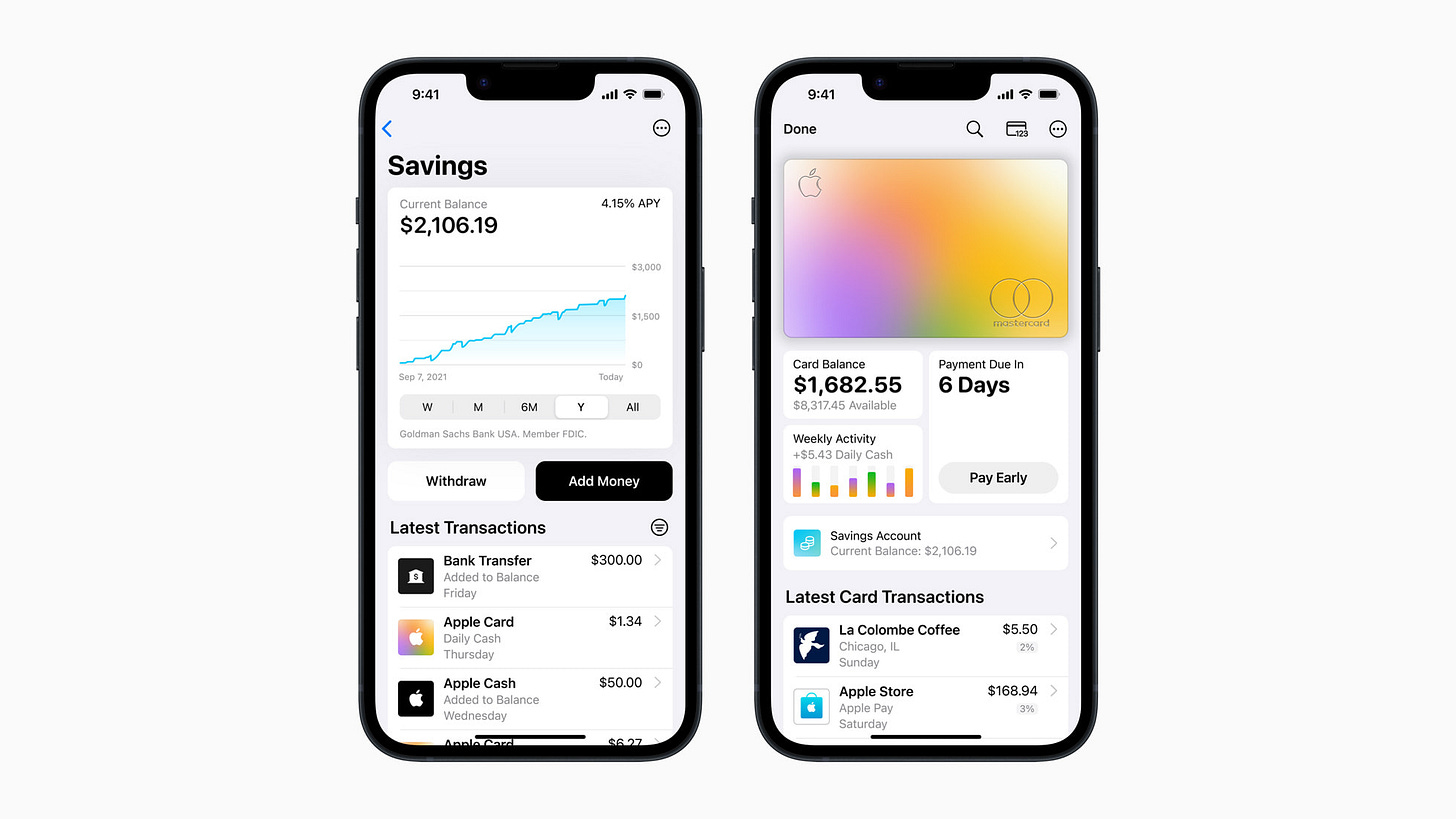

Call me a paternalistic socialist, but I’d support federal regulation that mandates that all bank savings accounts can’t be less than half of the federal funds rate. When interest rates rise, savings rates should rise too. But the average savings account rate is still less than 1% and most banks are making major money off customers who don’t shop around for a higher rate, or think that it will take too long to transfer funds.

Actually, it took me just three minutes. Apple’s Credit Card gives you 3% cash back on all Apple Pay purchases and those rewards are automatically transferred into a savings account with a 4.15% annual return.7 Connect your existing debit card to the Apple savings account and you can quickly transfer over whatever amount you’d like. (It is estimated that over $1B was transferred to Apple savings accounts in just the first four days after it launched.) If you want an even higher savings rate, Step has announced a 5% cash rewards program for all accounts with direct deposit.8

I hope you have a great Friday — and for those of you in the US, a relaxing long weekend,

David

Surely this has something to do with not having children. Increasingly, I’m hanging out with folks in their early 30s and mid-50s — on both ends of peak child-raising.

Really, it’s not a crisis. But it does feel like a notable transition — not unlike graduating from high school and moving out.

From Bloomberg: “Poor, busy millennials are doing the midlife crisis differently.” From Insider Magazine: “Millions of millennials could soon enter a midlife crisis. But they're going to spend and divorce less — and value experiences more.” Mashable warns its mostly Millennial audience that we are entering our “decade of despair.” Harper’s Bazaar has a whole series of middle-age commentary under the most generic of headlines: “40 is the new 40.” And then all the Millennial midlife crisis movies to come out in the past year: Fleishman Is in Trouble, Beef, One More Time, 40 Years Young, and Still Time.

I’m not denying that a small percentage of Millennials really did get the shaft. Stuck with student debt and humanities PhDs, they couldn’t afford to buy a house in their 30s, and now most of their salary goes to rent and childcare. While Twenge’s data shows that they make up a small (but vocal) minority of Millennials overall, they make up a disproportionate number of journalists (and my friends). And even those friends of mine are living a pretty great life, though it’s not the $200k professor salary and spacious midcentury home they dreamed about in graduate school.

For a thorough review of the research and theory, Chapter 1 of

’s excellent book Midlife offers a great summary.Largely depending, methinks, on when/if we have children and reach a level of financial stability.

I didn’t use my Apple Card until it integrated with Mint for budgeting and expense monitoring — which now works perfectly.

I'm too lazy to dig into it. But I do wonder if those charts showing millennials on par with previous generations for income and wealth are averages - which wouldn't capture the rising economic inequality that more recent generational cohorts are experiencing. The averages probably mis-represent the experience and don't reflect that higher fractions of wealth and income are concentrated at the top, leaving less for everyone else. That wouldn't be true for home ownership, tho although the level of mortgage debt would be interested to see.