Americans are richer, safer, and living longer than we were in 1995. But are we better off?

I mean, my life is better, no doubt. In 1995, I was an angry, directionless kid in a chaotic household. My teachers didn’t think I’d graduate from high school, much less find a stable career. It took a lot of community college, therapy, luck, mentorship, and hard work to find my footing.

But I shouldn’t project my own weird story. Consider the adult journey of your typical 1990s high school graduate:

Getting laid off during the Great Recession

The rise of the gig economy and hustle culture

Student loan debt and unaffordable rent & mortgages

Delayed marriage, homebuying, parenthood

Online social comparison and digital addiction

Increasing social and institutional distrust

So, let’s host a debate:

Obviously, we’re better off

We make more money and we’re wealthier. Median household income rose from $60,000 to $75,000, adjusted for inflation.1

We live longer, from 75 to 78 years.2 Cancer survival rates are up, while heart disease, smoking, and HIV/AIDS are way down.

We are safer. Violent crime is down significantly.3 Air and water quality have improved. Traffic fatalities are down despite more cars on the road.

We are more educated. College enrollment rose from 14.3 million students in 1995 to 19.1 million today.4

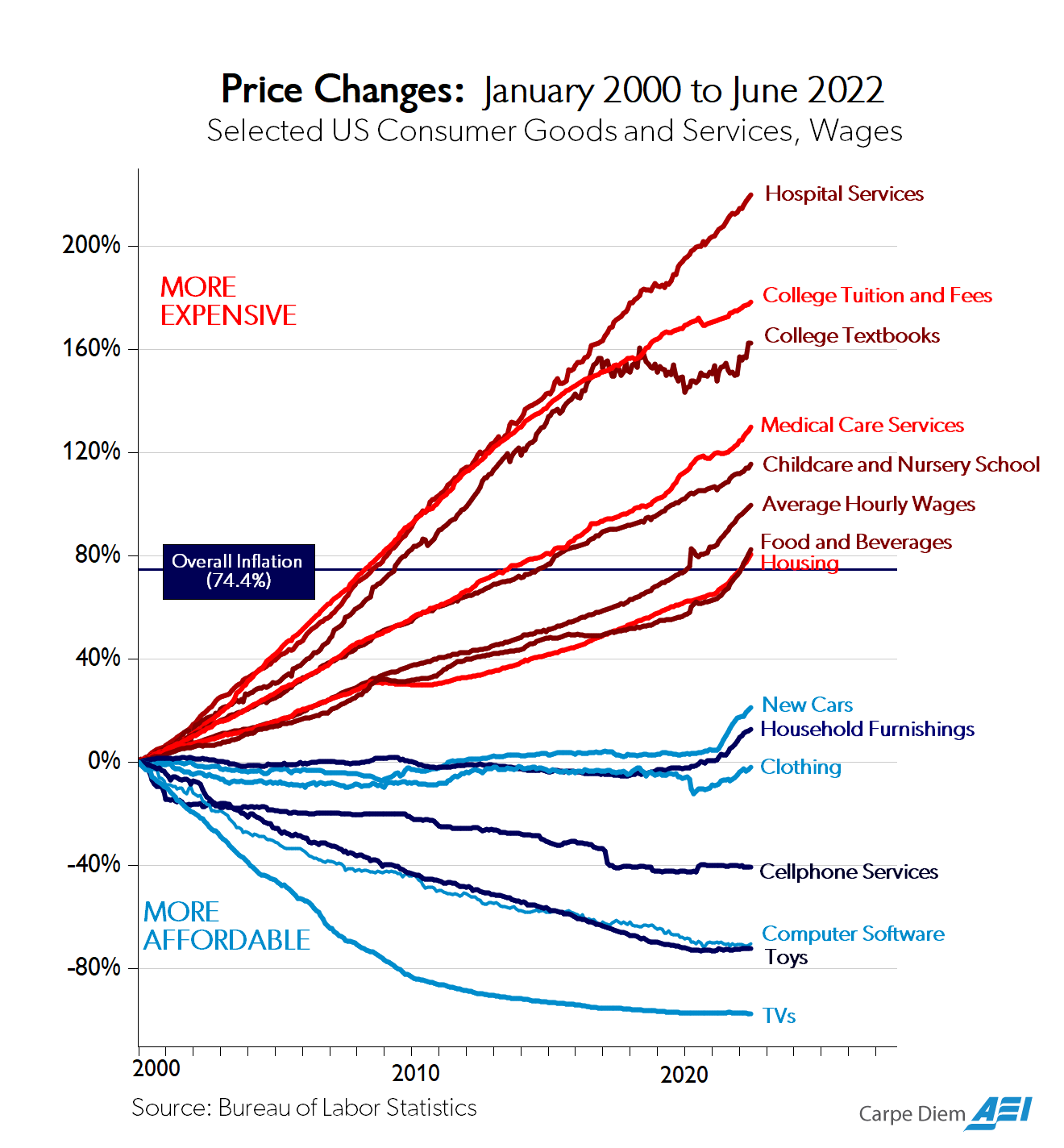

You can buy anything you need, (and lots of what you don’t). A 42” TV in 1995 was $3,000; today it’s $300.5

We are more inclusive. While far from perfect, it’s a better time to grow up female, Black, children of immigrants, disabled, and/or gay.6

No, we’re really not

U.S. suicide rates increased from 10.4 in 1995 to 14.2 in 2023 (per 100,000).7

Drug overdose deaths surged from 14,000 in 1995 to over 100,000 in 2023.8

Homeownership rates for young adults fell from 45% in 1995 to 36.3% in 2024.9

Trust in U.S. government dropped from 34% in 1995 to 16% in 2023. Trust in journalism, universities, and science has also declined.

Attention. Young Americans now spend more time on their devices than asleep; they check their phones 350 times a day.10

We’re addicted to outrage. Conflict entrepreneurs keep us hooked on content that makes us angry. Americans are exhausted by public discourse.

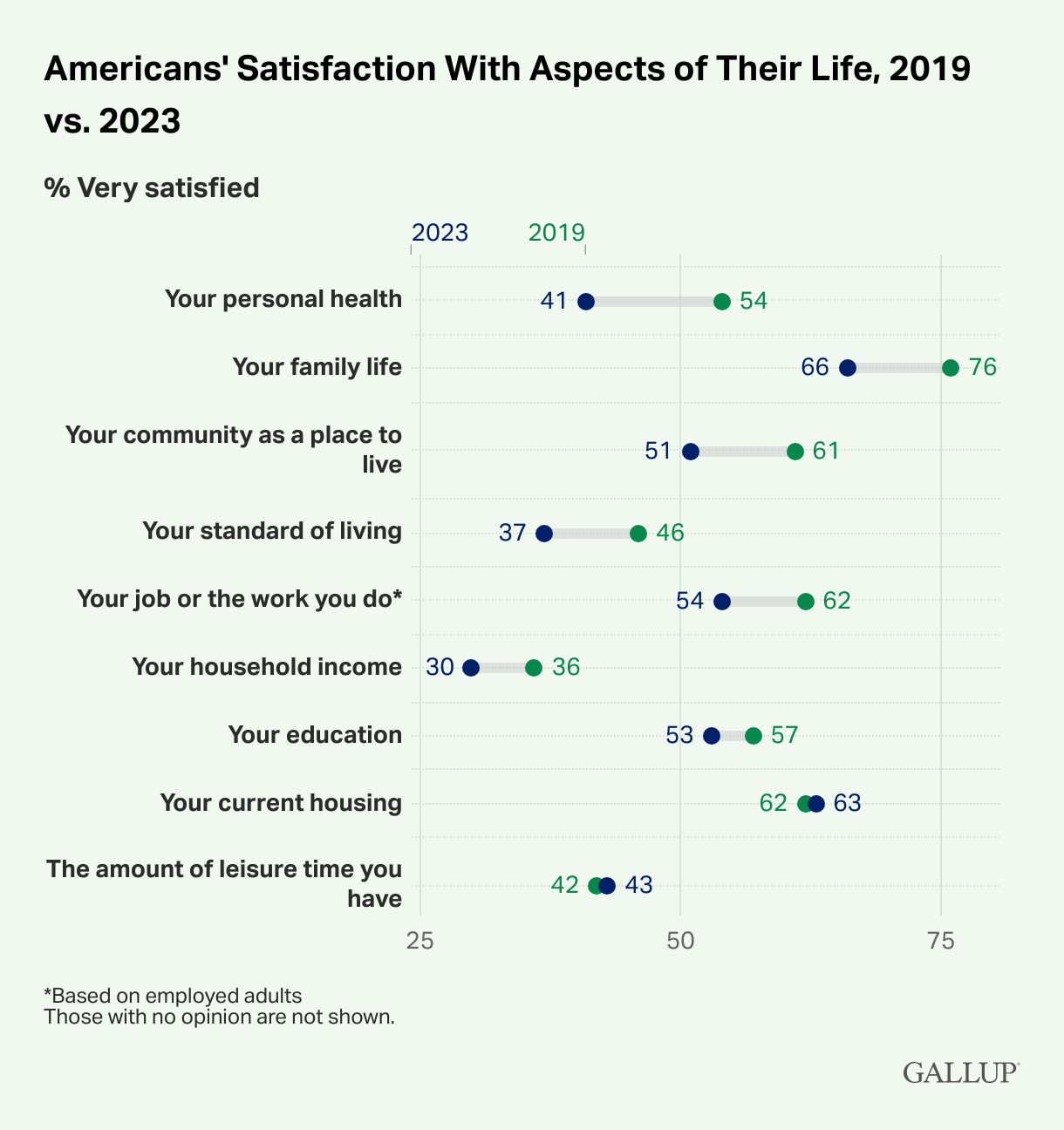

Despite having more wealth, safety, and entertainment, we are increasingly distracted, distrustful, and anxious.

Richard Easterlin made a similar observation back in 1974. The Easterlin paradox claims that societies become happier as they get wealthier, but only to a point. Beyond basic needs, additional wealth offers diminishing returns as we get used to the good life and keep comparing ourselves to others.11

The abundance agenda is not enough

So what can we do about it? Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson propose an abundance agenda, advocating for more and cheaper housing, healthcare, childcare, and education. I don’t disagree. We’ve democratized access to gadgets and entertainment while the basics are out of reach. We can afford big TVs but not small apartments.

Even with affordable housing, childcare, clean energy, and education, we won’t feel better. “The more we have, the less satisfied we are,” notes Anna Lembke, calling it the “plenty paradox.” Material progress doesn’t guarantee that we flourish. We've largely solved the problems of scarcity while creating new problems of connection, meaning, and attention.

We will still yearn for:

Creativity amidst artificial intelligence

Community, connection & belonging

Mentorship and personal growth

Healthy bodies, calm minds

Presence and attentiveness amidst endless notifications

Freedom from digital and chemical addiction

Restorative rest instead of anxious exhaustion

Connection with nature

Some of you will say that’s the realm of religion or podcasters, but not policy. I disagree. Just as we regulate tobacco and alcohol to protect public health, we can regulate addictive app design and teach K-12 students how to make long-lasting friendships. There’s a role for governments to help us become our better selves without becoming overly paternalistic.12

I’m looking for research and writing partners 🤓

The series will follow a basic structure. Some weeks, I’ll look at technologies that provide some benefits in moderation, but present risks in excess: porn, gaming, gambling, social media, chatbots, online shopping, ultra-processed foods, and vaping.

But I don’t just want to focus on mitigating the negative without offering alternatives. “Our phones are absorbing the dopamine and attention that we should be giving to our friends,” observes Derek Thompson. You can cut down your daily screentime from 7 hours to 3, but what are you going to do with those extra 1,500 hours each year?

I have some ideas. The series will also look into activities that people report enjoying and yet are cutting back on: playing sports, volunteering, hanging out, exploring nature, and taking vacations. I also want to do a deep dive on apprenticeships and vocational schools as an alternative career path into the middle-class.

I would love some research and writing partners. For each topic, I plan on spending a couple of weeks reading and synthesizing seminal research papers and relevant legislative proposals. I’m especially interested in working with people who might disagree with me.13 If that sounds like your idea of a good time (🤷♂️), please let me know!

Median household net worth went from $112k to $192k, adjusted for inflation. Most of these gains, as we covered last week, are from increased earnings among women. Adjusted for inflation, the median male full-time worker earns less today than in 1979

Though other countries are doing even better at increasing their average life expectancy.

From 684 per 100,000 in 1995 to 364 in 2023.

Though the cost of higher education and the burden of student debt increased more.

Check out Gwern’s list of “ordinary life improvements since the 1990s.” We have access to more information and entertainment than ever before.

This wasn’t on the original list, but it was the one point that every reviewer brought up.

In 1995, ~28% of teens reported feeling persistent sadness. By 2021, it was 44%.

Fortunately, there was a 27% decline in overdose deaths from 2023 to 2024. Hopefully, the downward trend continues.

In 1995, the median home price was $130K ($260K today); in 2023, it was $417K, far outpacing wage growth.

And 80.6% of Americans check their phones within the first 10 minutes of waking up. Young people now spend 8+ hours per day on screens compared to three hours of TV in 1995. In 1995, 2.8% of children were diagnosed with ADHD; As of 2022, it’s 11.4%. Prescriptions of stimulants (Adderall, Ritalin) in the United States doubled between 2006 and 2016, including in children younger than five years old.

Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers challenged the Easterlin paradox in 2008 with updated data that associates wealthier & happier societies. But more recent number-crunching shows a mixed picture with some of the wealthiest countries showing the biggest drops in happiness and mental health statistics.

Hey! Would love to help with this.

And isn't it weird? Even with data to ground ourselves, it's tough not to slip into our previous versions of ourselves when comparing this period to a previous one.

I'd love to dig deeper into this, especially as we look at ways toward a more (gestures wildly) just and joyful future.

I'm so glad someone wrote this. I would have used the year 1999.

The answer is flat out NO. We are not better off today in almost every area than in 1995(1999).

Graduated college in 1996. been through numerous lay offs through the decades. THIS is by far the worst job market I have ever seen.

When I graduated my starting salary was enough for rent, new car, paying my student loan, 401k, going out on the weekends and I still had money left over. This was the NORM for many if not all college graduates in the mid 90s. Late 90s, minus the dotcom bust, all other industries were fine.

Today everything, and I mean everything is expensive.