How we can have better candidates in 2028

Three practical reforms so that we vote for what want, not just against what we fear

In 2026, the United States will celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence from imperial monarchy. It has been a quarter of a millennium since the first constitutional democracy gave rise to the world’s richest, most diverse, and most innovative country.

How’s it going? Could be worse, but certainly could be better. We are stuck in a 50%-50% doom loop of negative polarization, with both parties invested in maintaining a political duopoly. They keep us so focused on fearing the other side that we dare not consider how to improve elections. And while there are real solutions that will bring us better candidates and reduce polarization, as I’ll describe below, not enough voters know about them.

If you’re focused only on your team winning and the other team losing, why would you care about changing the game’s rules to elevate the quality of play?

Democrats and democracy:

Ironically, exit polls show that the one issue Harris supporters cared most about was democracy itself:

But if their main concern was democracy — government by the people — then surely they would have voted for ballot initiatives to improve elections and reduce gerrymandering? For most Democrats, “pro-democracy” seems to mean little more than “anti-Trump.” Nearly every pro-democracy ballot measure nationwide was defeated, as both parties mounted opposition campaigns to maintain their power in selecting candidates. In Alaska, a slim majority even voted to repeal open primaries, handing their democratic power back to party control.

The problem: extreme and unrepresentative

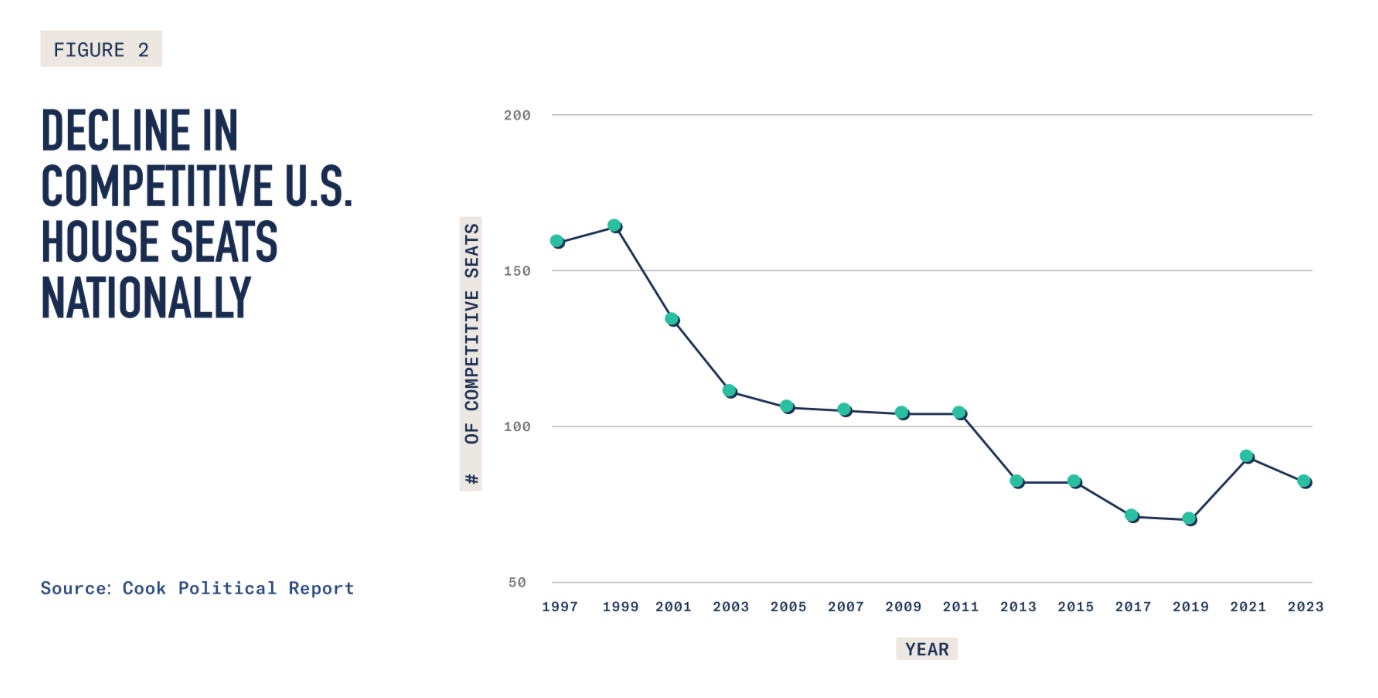

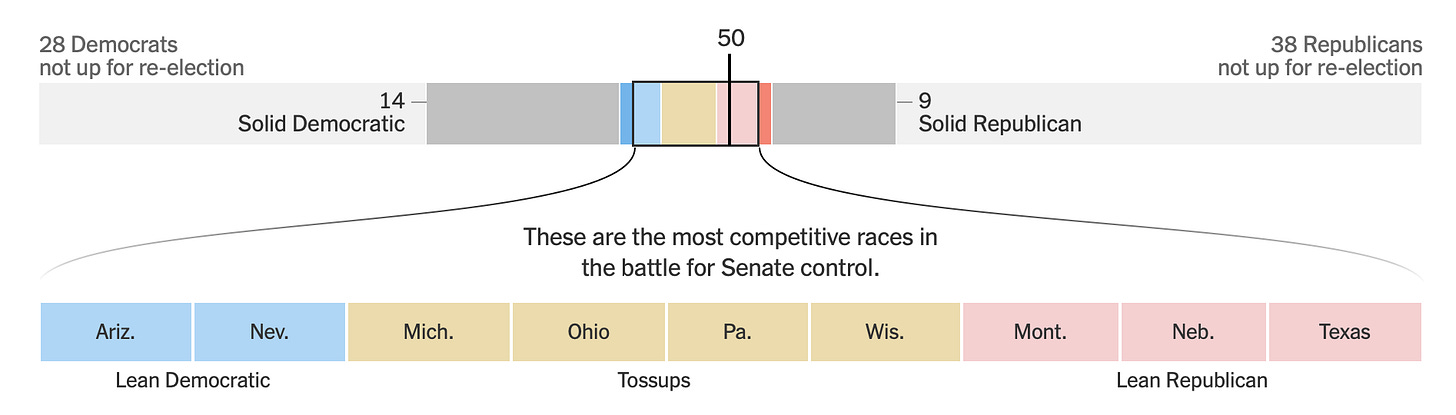

Every four years, the nation obsesses over who will become president, but only residents of a handful of states have any say.1 Similarly, thanks to decades of gerrymandering, 90% of House seats were effectively decided in primary elections by only 7% of voters. Of the 435 seats in the House, just 43 were competitive. This is worth repeating: for nine out of every ten representatives, the general election is essentially irrelevant—their seats are secured by the small minority who show up for the primaries.2

I could go on about our broken democracy, but you’d be better served by Freakonomics Radio’s most downloaded episode ever: Why Don’t We Have Better Candidates for President?

Some solutions: open primaries, ranked-choice voting, and independent redistricting

Three practical reforms provide a realistic path out of the negative polarization doom loop:

Open primaries allow every eligible voter to choose any candidate, regardless of party affiliation. Open primaries encourage candidates to appeal to a wider base—not just party loyalists.

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) lets voters rank candidates in order of preference, so you can vote for who you truly support rather than against who you fear. This reduces the “spoiler effect” and encourages positive campaigning; candidates must appeal to a wider range of voters to secure second or third-choice votes.

Independent redistricting commissions: Independent commissions draw fairer districts that reduce gerrymandering and lead to more competitive elections in which candidates must appeal to more voters — not just party loyalists.

The reforms aren’t without some critiques. The Denver Post editorial board, for example, argued that electoral reforms could cause confusion and erode the trust of voters in election outcomes. Others worry that empowering independent voters could benefit wealthier candidates; however, initial research disputes the concern.

Other pro-democracy reformers, like Lee Drutman and Matt Yglesias, say the three reforms don’t go far enough and advocate for proportional representation as a more transformative solution, though they acknowledge it’s not politically viable in the medium term. Open primaries, RCV, and independent redistricting, on the other hand, are achievable with just a bit more public support.

Having spent the past year deep-diving into their critiques and alternatives, I remain convinced that open primaries, RCV, and independent redistricting are the three best, most practical reforms to help us emerge from the negative polarization doom loop, where each side is motivated by fearing the other. The pro-democracy reform movement suffered a loss this week. Next month, we’ll gather in San Diego to reflect on our mistakes, sharpen our messaging, and grow the movement stronger than ever.

The macro trends are still on our side. A large and growing number of voters identify as independent. The country is more centrist than either of the parties. We’re exhausted by the hate, fear, and polarization. Eventually, we’ll do something about it. It may take 10 years, it may take 20, but hopefully we’ll get there by the time I re-open the Time Capsule!

PS:

The chart below shows the amount of time it took for a national reform movement to achieve federal legislation after the creation of a national organizing body. It’s a reminder that transformative change takes time.3

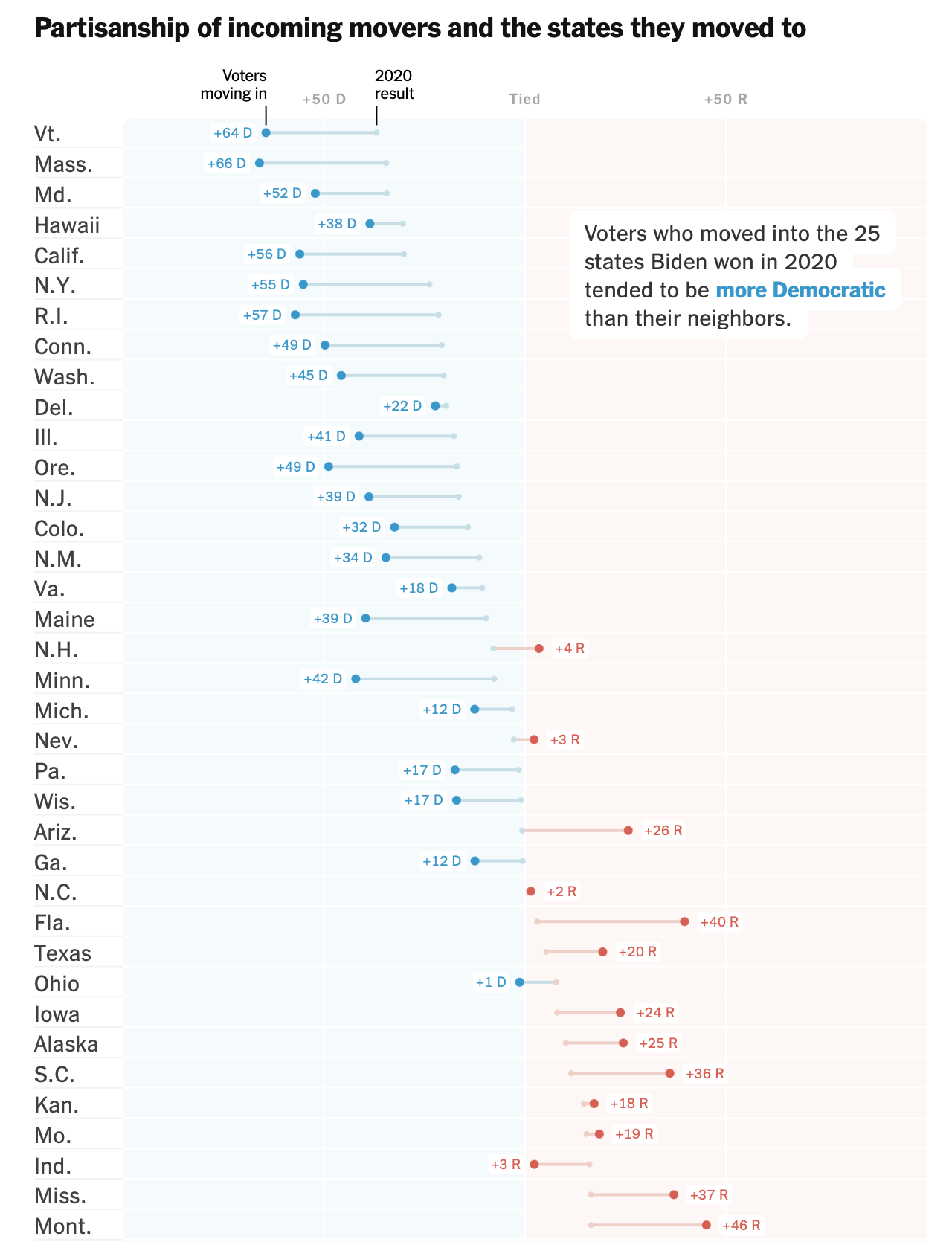

The Electoral College intended to equalize the power between smaller and larger states while appointing a body of “electors” to act as intermediaries so that only capable leaders assumed the presidency. Good intentions. Today, the electoral college means your vote for president almost surely doesn’t matter, and it contributes to The Big Sort, where liberals move to blue states and conservatives move to red states.

Lately, I’ve been reading about the widespread political corruption of the post-industrial Gilded Age from 1870-1900 and how it led to:

Populism among farmers who felt left behind by the industrial, urban transformation of the economy.

The Socialist Party of America formed by leftists opposed to worker exploitation in factories.

The Progressive Era of political reforms and women’s suffrage.

The parallels with today’s post-digital Second Gilded Age are too obvious to name. The post-industrial Progressive Era lasted 20 years from 1900-1919. I imagine that the post-digital Second Progressive Era will take just as long.

Surprised and impressed at how much insight you seek and pay attention to while living in Mexico. Ofc I don't expect you to turn a blind eye to all things America, it's not like you're living on Mars, but still impressive.

That being said, I'm curious as to the general reception of Trump's win in Mexico..? Lots of talk about immigration or anti-immigration actually.. wondering if Mexicans actually give a shit.

Politics 😩 I just want good government. As always thx for your hot takes.