#14 Regrets, revisions and amendments

Mistakes were made and things have changed

This is my 14th consecutive week of sending out a newsletter. They say it takes around 12 weeks for a habit to form, so I guess this is now a habit, and I’m grateful to those of you who have come along for the journey. I’m especially grateful to those of you who have sent me emails with encouragement, recommendations, and disagreement. This week’s newsletter is a collection of regrets, revisions, and amendments to previous editions. But first, a few paragraphs on nostalgia.

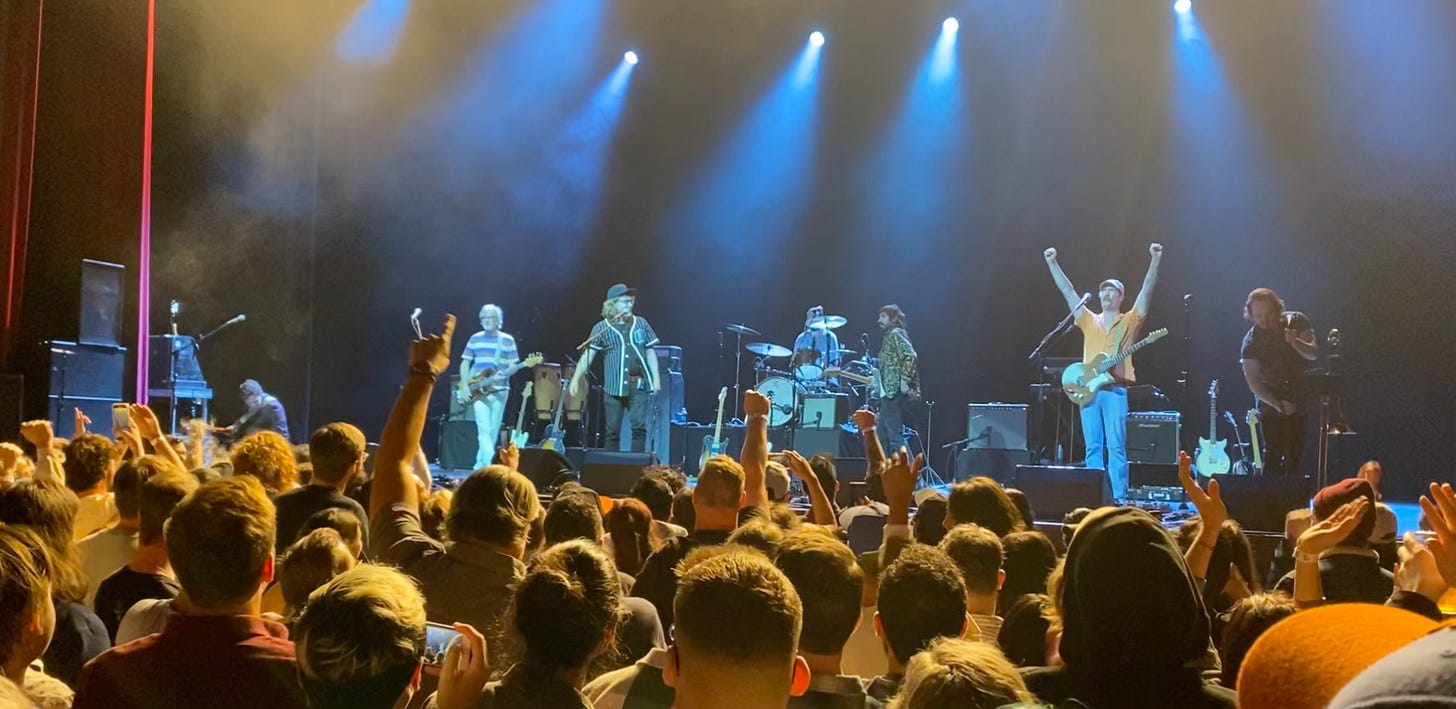

Nostalgia seeps into middle age. On Friday, Iris, Revaz and I saw Broken Social Scene live for their 20-year anniversary tour of the album You Forgot it in People. 2002 was an epic year in music. We were coming to the end of one cycle of musical invention: grunge, modern rock, techno, rap. And we were at the beginning of a new musical era, but we hadn’t yet settled upon the vocabulary to describe it: indie rock, electronica, hip-hop, shoe-gaze, post-rock, lo-fi. While we knew that the days of Lollapalooza and Lilith Fair were coming to an end, we didn’t know what would replace them.

When I heard Broken Social Scene’s first album, Feel Good Lost (2001), it was unlike anything else. It wasn’t just an innovative album; it was a signpost for music that would be heard through headphones, not speakers — and more likely on a digital playlist than a physical album.

What was I nostalgic for as I swayed back and forth with my fellow gray-beards listening to live music from two decades ago? It wasn’t just the remembrance of a favorite album from simpler times; I was nostalgic for hearing something that sounded unlike anything else I had heard before. I was nostalgic for the uncertainty, for not knowing how the music would evolve.

Today we are stuck in a recursive loop of cultural and technological stagnation. Our movies are either prequels or sequels. Our gadgets and devices are merely newer versions of what was released over a decade ago. Beyonce may be a cultural trailblazer, but the music still sounds the same.

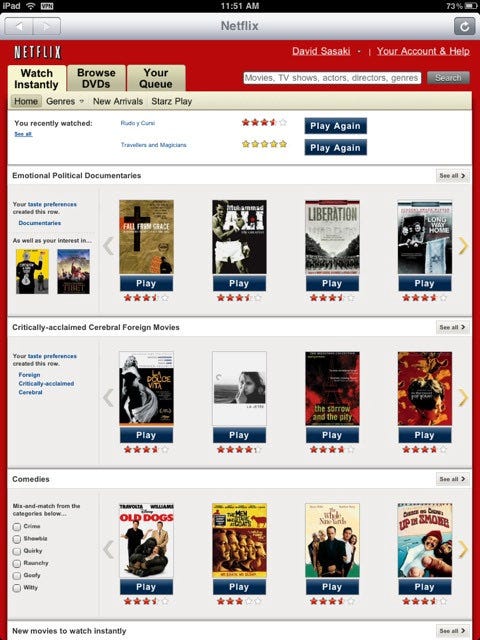

This morning Luis and I had a lovely Twitter Spaces conversation with Sara Watson and Grafton Tanner about the relationship between technology and nostalgia. (Next week we’ll publish an edited version to the podcast feed.) We explored whether our relationship with technology was better in the past than today, or if it’s just nostalgia playing its games of rose-colored remembrance. Sara mentioned the role of finance and that many of the most powerful technology companies today did not even have viable business models until around 2010. There was a brief decade of optimism and imagination between the Dot Com Crash of 1999 and the addition of the like button on Facebook in 2009. The lesson of the 1990s was that the internet wasn’t a place to make money. The internet of 2000 - 2010 was a place to make art and make friends via LiveJournal, blogging, Tumblr, Wikipedia, Flickr, Last.fm and so many other relics of the fossilized past. We thought the internet was built on love, as Clay Shirky described it back in 2007.

Nostalgia, I have learned, can be both escapist and reflective. It can inspire curiosity about how we experienced the past with the benefit of hindsight. And it can provide a salve of comfort, control, and certainty when we avoid the news to rewatch an episode of Friends. As time speeds up, nostalgia is a way to allow our future selves to revisit today’s uncertainties with all of the wisdom and experience that we have yet to accumulate.

Perhaps we should be grateful that we tend to focus on the pleasure of the past while we anticipate pain in the future. It must give us some evolutionary advantage to be mindful of threats on the horizon while we take pleasure in revisiting the good old days. The utopia of the past may be a mirage, but it’s a mirage that offers us a foundation to build on in the future.

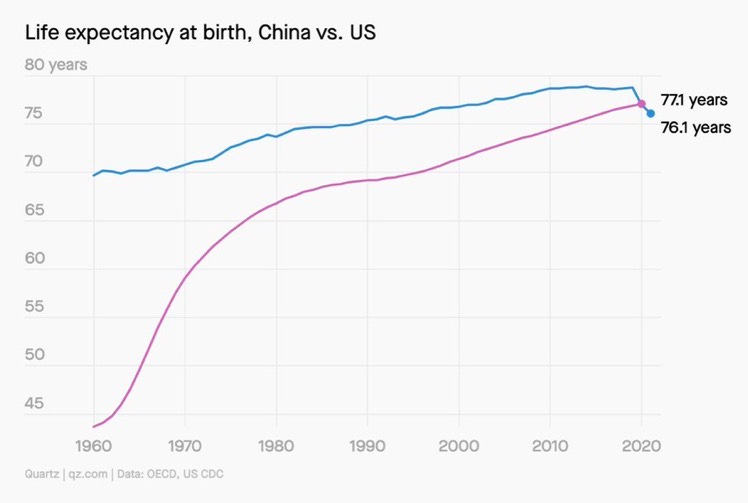

Revision: Life expectancy

In newsletter #8, I marveled at the longevity of my grandmother, who turned 93-years-old, and how the average life expectancy in the U.S. increased two decades from the time she was born to today. Twenty years of extra living! What a gift. Of course, the very next week the media was full of headlines like “U.S. Life Expectancy Falls Again in ‘Historic’ Setback” — with an especially stark drop for Native Americans. As we approach the 250th celebration of U.S. independence, we now live in a country where Native Americans on average live ten years less than everyone else. And there doesn’t seem to be much urgency to do anything about it. Meanwhile, in China:

Regret: Race & Xenophobia

A friend kindly asked if I was minimizing the role of race when I emphasized in newsletter #12 that black South Africans are xenophobic against black Nigerians and brown Indians are xenophobic against brown Bangladeshis. That wasn’t my intent. A British acquaintance recently described to me with great annoyance how her neighbors and friends mobilized to offer their homes to Ukrainian refugees upon Russia’s invasion when they would never consider doing so for Syrian or Yemeni or Ethiopian refugees. Clearly race factors into who we welcome and who we exclude. And while we have few examples of lighter skin refugees seeking amnesty in darker skin countries for comparison, there are a couple of fascinating alternative histories when there were serious proposals to resettle European Jews to Uganda in 1903 and to Madagascar during WWII.

Amendment: We’re all porn stars now

Iris and I were discussing Hot Money, the 8-part podcast series about the porn industry that I mentioned in newsletter #6. We confessed our surprise that the porn actors featured in the series were so relatable and articulate, and we started to question what is it that makes someone want to work in porn. The more we talked about it, the more I realized that we are all porn stars now. Instagram is essentially an amateur, unpaid, soft porn platform. Each week I thumb through hundreds of photos and videos that certainly would qualify as soft porn, at least by 1980s standards.

It got me thinking about the parallel between amateur porn and amateur writing. A lot of people must share photos and videos resembling porn because they enjoy it, just like many of us write for free because we enjoy it. And platforms like OnlyFans and Substack now allow porn actors and writers respectively to make money if they can convince their subscribers to pay. While mainstream culture may prize writing over sexual demonstration, pageviews tell the truth about where we place our attention. I certainly don’t judge if someone wants to show their body and someone wants to look at it and there’s a financial transaction in between.

I’ve got one more regret to offer about my take on masculinity from newsletter #8, but this week’s edition has gotten long enough.

Have a great week!

David